Read Sam's book

How Congress Can Better Support

- or Get Out of the Way of -

Innovation

INTRODUCTION: A FEW “FIRST PRINCIPLES” FOR SENSIBLE TECH POLICY

While many unique issues emerge throughout technology, a few basic principles seem to apply broadly as we consider the broad range of congressional options:

- In a global war for talent, our immigration and workforce policies must reflect that focus. We can have both a secure border and a sensible, pro-immigration policy essential to both innovation and American values.

- The cost of congressional indecision can be every bit as great as the impact of a poor decision. Where Congress fears to tread, others rush in to regulate—state legislatures, the Eurozone, the courts, and federal agencies—often in very unpredictable ways. Congress needs to act—and in such areas as data privacy, child online safety, AI, and cryptocurrency, enacting a federal statutory scheme can provide a more comprehensive, rational alternative to the patchwork local and international regulations that we see today.

- Congress must have greater sensitivity to how its laws—whether in the tax code, intellectual property, or antitrust—can create barriers or vehicles to private investment in research and development, particularly in early-stage companies that form the backbone of our innovation economy.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) will transform our economy and our lives in ways unlike any other technology in memory. Congress needs to step in to address the negative outcomes–fraud and malicious use of AI– without meddling in the regulation of the technology in ways that will undermine innovation necessary for medical research, climate change mitigation, and a host of other critical uses.

- The Defense Department cannot procure a ship in the same way that it procures software and advanced technology. To reduce wasteful spending and accelerate our fighting forces’ technological transition, Congress must authorize a more nimble approach than traditional procurement programs enable.

Table of Contents

A PRO-WORK AGENDA FOR IMMIGRATION REFORM

As a college freshman at Shandong University in Quindao, Eric Yuan had a problem: he had left his girlfriend and family behind in his hometown of Tai’an, hours away. The long train ride made it difficult to see his girlfriend, so he took a particular interest in developing videotelephone software to engage with her via video chats.

When a young Yuan heard Bill Gates speak during a tour of China in 1995, he became inspired to come to the U.S. to launch a career in technology. Eric had another problem: a Chinese student with few resources would face tall odds of successfully immigrating to the U.S.

He spent the next two years seeking a U.S. visa, applying—and failing—eight times. On his remarkable ninth attempt, Eric succeeded. He joined a U.S. startup, Webex, that developed video conferencing software, and a decade later, found himself at San Jose giant Cisco. When Cisco management declined to embrace Eric’s smartphone-friendly video conferencing tool, he left Cisco in 2011 and decided to launch his own company.

Zoom was born. Despite the best efforts of our immigration system to bar his entry to the U.S., CEO Eric Yuan today employs more than 7,000 U.S. citizens in Zoom’s San Jose headquarters and throughout the country.

Thank goodness for ninth tries—and for distant college girlfriends.

High-Skilled Immigration and Our Valley’s Future

Eric’s story is remarkable, but hardly unique. About half of our venture-funded startup founders came to the U.S. from another country.[1] In the hundreds of conversations I’ve had with employers in Silicon Valley, probably 80% cite immigration as a primary constraint on their ability to grow and succeed in the U.S.

The urging of venture capitalists John Doerr and Ted Schlein that we “staple a green card to the diploma” of every STEM graduate has become trite but remains true: it would make great policy.[2] We should want brilliant, ambitious people from around the world to contribute here, rather than going back to India, China, or elsewhere to compete against us. Canada’s forward-looking high-skilled immigration policies, for example, have lured more than 45,000 foreign-born graduates of U.S. colleges between 2017 and 2021.[3] We’re educating the best and brightest, and they’re creating jobs in other countries. We can blame nobody but ourselves.

Of course, this doesn’t even account for the many bright young minds educated abroad. India graduates millions of young people every year with college and advanced degrees, roughly one-third of whom go unemployed for many months after graduation—and their unemployment rate among college graduates exceeds 13%.[4] According to a 2022 Macro Polo study, 47% of the top artificial intelligence developers originated in China, with only 18% coming from the United States.[5] Due to stringent immigration policy, particularly the tightening of restrictions and availability of H-1B visas for high-skilled immigrants, Chinese AI and software developers increasingly remain in China: 28% in 2022, up from 11% in 2019.[6] Rather than enlisting them to boost American innovation, their exclusion propels our Chinese competitors.

Far from taking jobs, immigrants create jobs.[7] Economists widely agree that they help to create new technologies that accelerate economic growth. They consume goods and services that support many aspects of our economy. High-skilled immigrants, in particular, are 80% more likely to start new businesses than native-born Americans.[8]

Other countries get it. Canada, Australia, and Chile have created “startup visas” to lure entrepreneurs to their shores. In the U.S., a similar proposal found its way into the House-enacted version of the CHIPS Act, but did not make it through in the Senate. U.S. visas exist for investors, but not for the company creators—the entrepreneurs themselves–who merely seek 30-month “parole” periods under the International Entrepreneur Parole program. The creation of a “startup visa” in the U.S. is long overdue.

Our education system consistently fails to produce a sufficient number of graduates with STEM degrees to satisfy the demand for high-skilled talent among our leading industries.[9] The much-heralded CHIPS Act has catalyzed new investment in advanced chip manufacturing in the United States, but companies roundly report that they lack the skilled STEM workers to staff the fabs and labs.[10] Intel has reported just the initial phase of building two chip factories in Ohio will require 3,000 new skilled workers, and TSMC relies on bringing thousands of Taiwanese manufacturing workers to Arizona to get its new fab online.[11] To be sure, we need to do far more to boost homegrown talent, beginning with improved access to education. I discuss one idea—deploying a tax credit to lure tech investment into our community colleges—in the “Education” chapter of this book. We can also do far more to boost interest in STEM among American-born students. But even if we’re wildly successful in aligning our educational system with a fast-changing private sector economy—no minor feat, since our educational system is primarily controlled by thousands of state and local agencies and districts—we’ll see concrete benefits in about two decades. In the meantime, technology races ahead.

Unfortunately, federal law hasn’t caught up to reality. Congress last adjusted the 140,000 cap for employment-based visas a quarter century ago in legislation authored by the late Senator Ted Kennedy. Since then, our population has grown 35% and our economy 123%.[12] In the last four years alone, the rate at which a qualified applicant may “win the lottery” for an H-1B visa has declined from 46.1% in FY 2021 to only 14.6% in FY 2024.[13] A promising effort with some bipartisan support has emerged in the Immigration Visa Efficiency and Security Act of 2023.[14] Although the bill remains stuck in committee, the next Congress must push it ahead to expand access to high-skilled visas, particularly by eliminating a peer country cap for employment based immigrant visas crucial for alleviating the backlog of visa applications from nations such as China, India, and Mexico. Some softening of provisions regarding individuals from “adversary states” will be necessary to make this legislation impactful for tech employers in the Valley, but this bill offers a good start.

For permanent residence or citizenship, the picture appears even more bleak: our system imposes multi-year and even multi-decade waits on immigrants. Employment-based green cards remain subject to such stringent caps that the U.S. is only today processing applications from Indian nationals submitted in 2012.[15] Unbelievably, today’s applicants face even longer waits. Families that have spent many years living here under a wage earner’s renewed work visa do so under a cloud of uncertainty about their futures that affects every decision, from employment to marriage to child rearing and home purchasing. We must do better.

A More Secure Border—Sensibly

Any conversation about immigration inevitably turns to the border. It’s important to return to our first principles: the United States can have both a more secure border and more immigration. It’s critical for our nation’s future that we have both.

Border security has vexed every presidential administration in memory, and none more so than President Biden’s, but it’s hardly a new problem. As a federal prosecutor in the late 1990s, I prosecuted criminal organizations engaged in human and drug trafficking along the border in California, I became amply familiar with the criminal industry that exploits human despair for profit. Of course, many other factors drive the migration patterns across our southern border – poverty, a collapsing civil order in Venezuela, drug-related violence in Mexico, and the like.

The Border Crisis

Clearly, we need to do more to enforce the law and address the humanitarian crisis at the border. For the second consecutive year, more than 2 million people crossed the U.S.-Mexico border illegally in 2023.[16] Hundreds of people die each year making the perilous journey through the desert. Beyond the traditional pattern of Latin American families fleeing violence and poverty, apprehension data reveals a disconcerting increase of crossings in the (albeit still very small) number of people on terrorist watchlists from elsewhere in the world.[17] National sovereignty entitles us to know—and national security requires us to know—who is entering our country.

Many more people without documents come and claim asylum. The flow of asylum claims has overwhelmed American immigration courts, with the backlog swelling to more than 1 million over the last decade—all part of a total caseload of 3.4 million backlogged cases in our U.S. immigration courts.[18] Final determinations require many years, by which time most applicants merely “fade into the population,” working and living here illegally.

To be sure, the border appears rife with drug trafficking as well, and these drugs constitute a serious peril to Americans: synthetic opiates like fentanyl and stimulants like methamphetamine account for nearly 110,000 drug-related deaths each year.

Yet drug traffickers aren’t who we think they are. Roughly 90% of fentanyl is smuggled across the border by U.S. citizens, not immigrants, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials,[19] often paid by trafficking organizations to sustain their own addiction.

Why U.S. citizens? Most drugs move through ports of entry in places like San Ysidro and Mexicali where drug trafficking organizations can much more easily monitor their valuable cargo to mitigate theft and loss than when contraband travels by boat or over the sea. At the ports of entry, traffickers don’t want to risk losing the load to confiscation by having the driver detained by inspectors. Drivers and passengers who are U.S. citizens avoid “secondary inspection” at a much higher rate than non-citizens, obviously. Better enforcement against drug trafficking at the border, then, has less to do with immigration and much more to do with inspections. U.S. inspectors scan only 2% of cars and 14% of trailer trucks at the border, an inspection rate that appears plainly inadequate to stem the flow of drug contraband.[20] U.S. immigration courts.[21] Final determinations require many years, by which time most applicants merely “fade into the population,” working and living here illegally.

To be sure, the border appears rife with drug trafficking as well, and these drugs constitute a serious peril to Americans: synthetic opiates like fentanyl and stimulants like methamphetamine account for nearly 110,000 drug-related deaths each year.

Solutions at the Border

In this factual context, some solutions for the border crisis begin to come into focus—and none of them require separating children from their families, nor housing children in cages. For example, to improve detection rates of vehicles smuggling drugs at our land ports of entry, we must invest in biometrics and better vehicle scanning technology. We need more inspectors at the ports of entry, and more Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents with smaller investigation caseloads. The last bipartisan border package contained provisions to accomplish several of these things, until Republican support for their own negotiating position wilted under pressure from former President Trump. To improve detection of human trafficking through the desert and outside of the ports of entry, we also need more border patrol and better technology. We can start by supplanting aging cameras with low-cost sensor and communications equipment, such as integrated fixed towers, remote video surveillance systems, tethered aerostats, dismounted radars, and other technologies.

We can also do more south of the border. Most superficially, we could better leverage behavioral insights with marketing campaigns south of the border to discourage illegal crossings by emphasizing the likelihood of apprehension and detention. We could dedicate more resources to investigate, arrest, and prosecute criminal gangs involved in human trafficking. As President Biden emphasized in U.S.-Mexico discussions in April, marked improvements at the border result when we persuade, cajole, or incentivize Mexico to step up to its responsibilities along its southern border with Guatemala and Belize.[22]

Longer-term strategies are also critical. We must build stronger partnerships among U.S. companies seeking to improve supply chain resilience by next-shoring manufacturing of everything from memory chips to photovoltaics in Mexico and Latin America. They can reduce geopolitical risks and trade secret theft by relocating from China, while boosting jobs and opportunities south of our border. Using these job creators as carrots (and their withdrawal as sticks) for Latin American governments that demonstrate performance in reducing corruption, promoting free and fair elections, and the like, can do much to improve the quality of life for millions who might otherwise flee to the U.S. in despair.

Finally, we need to enforce the law. We are a nation of laws, and nobody—neither U.S. presidents nor undocumented immigrants—can be allowed to violate U.S. laws without consequence. We don’t need to separate children from their families for a safer border, and we certainly don’t need more press conferences, demonizing, and outrage. We need to enforce the laws, and focus on what works.

Beyond Tech: Immigration for the Rest of Us

It’s not just tech employers who want to boost legal immigration; the heartland should care as much as the coasts about attracting the best and brightest to our shores. The reality is that virtually every industry—agriculture, manufacturing, health care, construction, elder care—needs more legal immigrants.

Currently, the U.S. has about 8.2 million unfilled jobs; we simply lack enough native-born workers to fill them.[23] To put a finer point on it, we lack sufficient native births to even replace our current population, a circumstance that would have left my fecund Sicilian, Irish, and Mexican ancestors puzzled. Indeed, immigrants are projected to account for 88 percent of U.S. population growth through 2065.[24]

The implications of this reality are considerable and broad. First, workforce shortages make goods and services cost more. For example, a majority of economists empaneled in a recent Wall Street Journal analysis opined that Trumpian policies to crack down on immigration would more likely boost inflation in future years.[25] For most American families, those increased costs don’t merely affect the margins.

Consider the extraordinary struggles of many families to shoulder elder care. Severe shortages of nurses, nursing assistants, home health aides, and personal care aides make elder care elusive for many, and have driven costs upward for those who can afford the help. In 2022, more than half of nursing homes reported that they limited new patient admissions due to nursing shortages.[26] One 2017 estimate from MIT researcher Paul Osterman predicted a shortfall of 151,000 paid direct care workers by 2030, a gap that will more than double in the following decade.[27] Immigration, which already provides one-quarter of America’s elder care workforce, can help. Of course, boosting Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates (with the goal of supporting higher wages of care providers) would go a long way as well to reduce turnover and attract a larger direct care workforce.

Speaking of Medicare, the financial viability of our Social Security and Medicare systems depends on a steady supply of legal immigrants to support our rapidly aging U.S.-born population. Both systems face an imminent challenge of insolvency; Social Security’s OASDI trust fund will deplete in 2034, at which point the incoming funds will cover only 75% of the promised benefits. For Medicare, the Hospital Insurance trust fund will deplete by 2031. Most immigrants actually support both systems’ financial sustainability.[28] Immigrants with permanent status and dual intent temporary visas must pay payroll taxes to finance each fund. Even many undocumented immigrants who work in formal sector jobs using a false Social Security number pay an estimated $13 billion, for which they will never claim benefits.[29] Although many long-term immigrants also receive Social Security benefits after they’ve contributed to the system, their youth provides a net fiscal benefit to the Social Security system in the long run, so higher immigration actually reduces the long-term deficit in the system.[30]

Of course, underlying these estimates is the well-founded assumption that working immigrants contribute to economic growth—and that we could have more growth with more working immigrants. The Bipartisan Policy Center produced a study last year that estimated that clearing the current green card backlog of 7.6 million applicants—both by raising statutory caps and appropriately staffing the processing of applications—would produce about $400 billion in additional GDP in the U.S. each year.[31] About 71% of the GDP benefit would come from simply changing the restrictive rules and caps that constrain so many immigrants from working here and earning legal wages.

Beyond these economic arguments, immigration remains essential to the American character. The immigrant ethos—to sacrifice, risk, save, and invest for the benefit of future generations—has defined and inspired the American Dream. This ethos has inspired the remarkable trajectory of millions of families, including those of my own Italian, Mexican, and Irish ancestors. We know these stories well from our own families: from the grandmother who sacrificed to help her grandkids attend college, or the father who saved to enable his daughter to buy a first home. This ethos provides a powerful antidote to the less disciplined elements of American culture.

Our 11 Million Undocumented Neighbors

Esteban (whose name I’ve changed) is undocumented, and owns a restaurant near my San Jose home. He has tried unsuccessfully for three decades to legally “adjust his status” under Section 245 of the Immigration and Naturalization Act, without avail. In that period of time, he has raised a family, built two businesses, employed dozens of (mostly U.S. citizen) residents, supported his community, and paid several hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes. I wrote a letter to support his most recent effort to legalize his status.

I have other neighbors without legal status who have similarly raised families for decades. One is a widely beloved coach in a youth soccer league, and another served as a teacher’s assistant in a local school system, and recently saw her oldest daughter graduate from college—a feat about which she could only dream.

What about the fiscal burden of illegal immigration on our country? Well, undocumented immigrants pay taxes—whether sales taxes, utility taxes, payroll taxes for retirement benefits that they’ll never receive, and the like —totalling $100 billion last year.[32] Undocumented immigrants typically pay about 26% of their income in taxes—roughly the same as the rest of us—in part because they don’t qualify for any deductions or tax credits. Obviously, most do not pay income taxes; if we legalized the status of the thousands of immigrants who are illegally working here, we could generate another $40 billion annually for the federal and state budgets, while many of those workers would also earn higher wages.[33]

We must create a legal path for these longstanding members of our community. For those who have, say, worked and lived in the U.S. for a decade, without committing any crimes independent of their immigration status, we must create a path to citizenship. That may include the payment of a fine or fee, as some proposals have required—but it must be a viable path.

I frequently hear the complaint that “My mother wanted her turn to immigrate, why can’t they do the same?” The short answer is that there is no “turn” to wait for. In the views of many immigration experts, “There are virtually no pathways for permanent legal migration for those with neither close family ties in the United States nor a college degree. And even with close ties, it takes years of waiting to get to the front of the line.”[34] For example, for Mexican relatives of U.S. citizens with the highest family preference, the State Department is currently processing applications filed in 2005.[35] Twenty years later, many of those applicants have died. For the 11 million who have built their lives and families in the U.S. for decades, we must provide a viable legal path.

Finding A Path in a Divided Congress: A Pro-Work Immigration Agenda

How do we “sell” immigration in a divided Congress? Many members of Congress don’t embrace the value of immigration, or they fear the more populist and nativist groups that form their political base.

The American people feel differently. Contrary to the partisan rhetoric and the outrage machine of social media, there’s a lot about immigration that Amerians can agree on. Most Americans of both parties want both a secure border and a fairer immigration system. An October 2022 poll shows that legislation to create an earned path to citizenship for millions of Dreamers and boost support for border security would earn overwhelming (71%) support among Americans, including a majority (58%) of Republican voters.[36] A large majority of Americans of all parties want to see more high-skilled immigration as well.

Nearly universally, we all value work. We could start with what I’ll call a “pro-work” immigration agenda. Of course, border security would comprise part of the package, but the legislation would need to combine several elements that address the serious human gaps in our economy, from talented college students to caregivers of our elderly. While a more comprehensive package would require far more detail than can be described below, a few elements might include:

- Sensible border security measures, as suggested above.

- Passing of the Dream Act, to provide DACA recipients who continue to work or get schooling to have a path to citizenship.

- Promoting high-skilled immigration through:

- Increasing caps on both permanent (EB-1 through EB-5) and temporary (H1-B) employment for high-skilled employees,

- Creating a startup visa, to enable founders of high-growth companies to launch their companies in the U.S.,

- Allowing employment-based visa holders to apply to become lawful permanent residents.

- Creating legal paths to immigration in the many fields where we face critical and chronic labor shortfalls, e.g.,

- Enabling physicians studying in the U.S. to have a permanent pathway (i.e., permanently authorizing the Conrad 30 waiver program),

- Creating a new visa for direct care workers to address our chronic shortfalls in the labor supply of elder and child care,

- Establishing a pathway for migrant farmworkers in the United States to earn legal status (i.e., reforming the H-2A visa program),

- Creating a new temporary non-immigrant visa category for year-round work in industries experiencing chronic occupation shortages.

- Boosting the economic productivity and self-sufficiency of those immigrants who are here, by:

- Mandating approval of work visas for the thousands of asylum recipients eager to work to support themselves and their families,

- Granting Temporary Protective Status and Work Permits to spouses of citizens and lawful permanent residents, to enable thousands of spouses to enter the workforce,

- Authorizing adjustment of status of undocumented individuals and their families where a breadwinner has worked (with immunity for employers who sign declarations admitting as much) for at least a decade in the U.S..

- Increasing caps on legal immigration annually by a modest percentage (up to 3%) to account for our growing economy and our shrinking native-born working population.

No one can say what it will take to get a comprehensive immigration reform package through this very divided Congress, but we need to restart this long-overdue conversation. I start it here: with an immigration program that emphasizes work, and highlights the value of immigration to our collective economic well-being.

THE COST OF INDECISION: REGULATORY PINBALL

Since the advent of the internet, Congress has responded to the head-spinning pace of technological change with rants, public hearings, finger-pointing, press releases, and…. inaction. In virtually every key area requiring attention—online child safety, digital privacy, cryptocurrency regulation, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence—we have seen an astounding absence of legislation.

Industry typically cheers governmental torpor, preferring that Congress stay out of its hair. Yet increasingly, I’m hearing complaints from leading innovators, academics, venture investors, and others about the legislative void. Why? Congressional indecision allows other actors to jump in—most of whom have no or little accountability to the American people, and some with interests inconsistent with those of U.S. employers and consumers.

For example, Europe has spoken. The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, has set a standard for personal data privacy, which states like California have sought to emulate. While many consider GDPR to provide a generally sensible approach, there are detractors as well. We cannot assume that Europe will always strike the right balance for the American economy, particularly as the U.S. has many more jobs affected by tech regulation than Europe ever will. Ceding policy leadership invites peril. In artificial intelligence, for example, the EU’s proposed regulations purport to constrain a largely American-led industry. There appears no assurance that European legislators will tweak their rules to accommodate the imperative of competitive innovation in a moment when many global actors—in China or Russia, for example—will simply ignore the regulations that bind responsible actors.

Within the United States, individual states will act on their own, independent of the federal government. That creates two challenges. First, the prospect of having to navigate a thicket of 50 separate sets of regulations handcuffs companies that genuinely seek to comply. Subjecting an industry to 50-state regulatory pinball particularly harms small startup innovators. Early-stage companies lack the resources to hire the hundreds of lawyers and regulatory experts at Google, Microsoft, or Meta, accelerating the concentration of power and market share among a small number of tech giants. Second, consumers remain unevenly served across the nation by states with varying levels of statutory protection, sophistication, and enforcement resources. Every American internet user should have the same privacy and fraud protections, whether they live in Mississippi or California.

Finally, federal agencies jump in where Congress fears to tread. In cryptocurrency and antitrust, for example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) concoct novel theories for enforcement without congressional authorization, leaving a trail of lawsuits behind—and a trail of defeats for both agencies. The cost and uncertainty imposed by unpredictable regulation has pushed the crypto industry offshore, leaving tens of millions of Americans subject to the whims of foreign regulators. The FTC’s approach appears to be freezing capital investment in early-stage life science companies. Regulation by litigation is not a winning strategy for the American economy.

I’ve identified three areas (out of several) where congressional action appears badly overdue. They provide a good starting point for a much broader conversation: (1) data privacy, (2) online child safety, and (3) cryptocurrency. Let’s consider each in turn.

Protecting Our Privacy Online

Data privacy has been a topic of debate in D.C. for a quarter century. In that time, every other G20 nation has enacted a data privacy law. The United States has not. Congressional inaction separates Americans from the 79% of global inhabitants who have the benefit of some national data privacy law.

Why the need for action? As users of the internet, we have turned from consumers to commodities. Firms have long sought to exploit our data in ways that should make us feel alternately uncomfortable and enraged. Companies—and governments—too often track, predict, and manipulate our behavior without our knowledge or consent. A few recent findings:

- Duke University researchers found that data brokers sell the data of U.S. military personnel for as little as 12 cents per record.[37]

- The New York Times reported that automakers share data on drivers, collected by their cars, with insurance companies that use the information to raise premiums.[38]

- A fertility tracking app shared users’ health information with other companies, including Google and China-based marketing firms, according to a 2023 settlement with the Federal Trade Commission.[39]

These examples alone should prod Congress to act, but additionally, rights to data privacy appear foundational for other areas of tech regulation, such as AI and online child safety. Congress would do well to get moving on data privacy.

In broad contours, a responsible approach to data privacy regulation would incorporate several basic elements:

- Data Minimization: Congress must establish a federal baseline for what data can be collected, and that baseline should reflect what the company needs to provide its service. Banks shouldn’t collect our health data, but should have our credit scores. Online retail vendors don’t need to know the number of children in our families, but may need our home addresses.

- Consumer Control Over Data: Consumers must consent to the transfer or sale of their data. They should have the right to see their own data, and a means to require a company to correct it, where it’s inaccurate. Too many of us have experienced the frustration of learning about an inexplicable downturn in our credit score because someone else used our Social Security Number, or a firm misreported a transaction to a credit bureau. With more sensitive data, such as information regarding pre-existing health conditions, consumers should have stricter protections that require affirmative express consent before third parties can access it. In some circumstances, consumers should be given the right to delete their data altogether. California has set a strong standard by establishing a registry for data brokers, and enabling consumers to contact brokers directly to request deletion, but the process remains clumsy with nearly 500 brokers on the site. In 2026, thanks to legislation authored by Senator Josh Becker, a consumer can delete all records through a single request to the California Privacy Protection Agency.[40] Advocates have sought to have the FTC play a similar role by creating a federal registry, but Congress has not yet granted it such authority. A federal regulatory role appears long overdue.

- Targeted Advertising: Consumers should have the ability to opt out of targeted ads they find undesirable.

- Anti-Discrimination: Companies must not be able to use racial or other ascriptive characteristics to discriminate against consumers, as we’ve seen too often historically in mortgage lending and insurance, for example.

- Data Security: Companies must be held liable if they fail to maintain strong security measures over the consumer data they keep. A single, robust national security standard must apply to every financial, business, governmental, or nonprofit institution that holds personal data.

- Private Rights of Action, with Sensible Limitations: Consumers should have standing to sue companies that blatantly violate basic privacy standards and exploit data for their gain. We might constrain the avalanche of lawsuits by only allowing for injunctive relief rather than damages in all but the most egregious cases, to reduce the ambulance chasing. Privacy protections, nonetheless, would appear toothless if dependent solely on enforcement by a federal bureaucracy that will almost certainly lack staffing and funding to meaningfully monitor the hundreds of millions of consequential daily interactions.

- A Compliance Pathway for Small Businesses: Europe’s GDPR regulation has generally managed to protect privacy well, but set standards that only Meta and Google can comply with relatively easily. Compliance costs to smaller businesses appear far more onerous, which unfairly benefits the large tech monoliths.

- Federal preemption: California and Illinois have passed laws with strong elements that merit inclusion in any federal statute, such as the creation of a private right of action. Yet the need for uniformity in a national approach to data privacy also seems self-evident: companies cannot reasonably navigate a thicket of 50 state laws, and American consumers shouldn’t have to speculate—and ultimately litigate—over which state’s laws should apply to protect their privacy rights. While privacy advocates in California will understandably express concern about preemption, the overwhelming majority of federal action should strengthen the uneven patchwork of privacy protections, not weaken it.

Many of these principles already constitute “best practices” for responsible corporate actors. Yet Congress has not reached agreement on what a data privacy measure should resemble; Republicans object to the creation of a private right of action, for example, and Democrats balk over preemption provisions. It is hard to imagine how a federal privacy law can be effective without both of those elements.

Few would expect action from this uniquely torpid Congress during a presidential election year, yet there is hope for privacy advocates: a bipartisan, bicameral draft proposal known as the American Privacy Rights Act (APRA). APRA has emerged from negotiations between the two leaders with the primary jurisdiction over matters of internet privacy: Senate Commerce Committee Chair Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and the Chairperson of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA). The draft that emerged in April embraced many of the primary elements outlined above, and more.[41] The proposal carves out businesses generating less than $40 million in revenue, but still covers the largest players in the market, plus 90,000 other entities that gather our data, including financial institutions, hospitals, nonprofit associations, retail vendors, and social media platforms.

Of course, promising compromises over data privacy have emerged before, only to fall victim to political wrangling. It will require principled compromise—nimbly navigating obstacles without losing sight of fundamental values—to make it law. If it does not reach the president’s desk in this Congress, I will push to make APRA’s passage a priority in the next one.

Child Safety and Social Media

Many threats lurk online for our children, particularly on social media platforms. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s recent release, The Anxious Generation, confirmed the anxieties of many parents by citing many studies showing that a smartphone-driven “great rewiring of childhood” has already caused an epidemic of mental illness. We have seen a doubling a suicide among youth between 2008 and 2020, which roughly correlates with the widespread adoption of smartphones and participation in youth-targeted social media. Threats to our children’s physical health—such as obesity and diabetes—also loom, as studies show a substantial increase in a child’s body mass index (BMI) based on their screen time.

Yet there’s more. The largely unspoken threat to our children lies in what we might call the “opportunity cost” of screen time. The ability of TikTok and Instagram to consume an average of 7 hours of an early teen’s attention each day comes at a great detriment to her focus on the many other priorities for her wellness and future success, like homework, in-person socialization, physical exercise, or tending to younger siblings. In Haidt’s words, “I call smartphones ‘experience blockers,’ because once you give the phone to a child, it’s going to take up every moment that is not nailed down to something else. It’s basically the loss of childhood in the real world.”

Congressional Inaction

Nearly the last statutory word on the public responsibility of online platforms was uttered a quarter century ago.[42] The Communications Decency Act, commonly known as Section 230, offered an expansive liability shield to online platforms and other “neutral” forum hosts from harms resulting from the dissemination of offensive or false information posted by third parties. In 1996, liability protection made some sense; Congress did not want lawsuits to choke this nascent technology before it could reach its economic and social potential.

In 1996, I was still a law student at Harvard, busily preparing “moot court” briefs on a case interpreting the recently-enacted Section 230 before a panel that included U.S. Supreme Court Justice Steven Breyer. Seven years later, I was a prosecutor in Santa Clara County, working with a multi-city team of police detectives in the Internet Crimes Against Children task force to protect kids from online pedophiles. I can recall thinking that the time for reform of Section 230 was already overdue–in 2003.

Two decades later, little has changed in the law, but much has changed in reality. Child safety comprises one of several issues fueling demands for better content moderation on social media platforms. Others—including fears about disinformation and manipulation from foreign adversaries and domestic fraudsters—also deserve immediate attention. Yet child safety seems to provide an optimal starting point, given its urgency and ability to unite Republicans and Democrats.

This April, a rare whiff of bipartisanship enabled the enactment of a law that may force the divestment of TikTok by its Chinese owners, ByteDance, in an attempt to prevent the data collection of young users deemed a national security concern. That legislation has since become the subject of litigation, as TikTok has argued that it amounts to an impermissible prior restraint on speech under the First Amendment, and many legal scholars doubt its survival of judicial scrutiny.

Three months later, a bipartisanship spirit again prevailed as the Senate approved the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA) by an overwhelming 91 to 3 vote. The bill has some sensible objectives, such as to limit features that encourage cyberbullying, harassment, and glorification of self-harm. It would also require tech companies to establish default settings that would reduce compulsive use, and mitigate safety and privacy concerns. Yet the language of the bill has also invited detractors, and virtually no expert on the Hill expects passage in the House, given the long line of opponents—civil libertarians, Big Tech platforms, right-wing activists, LGBTQ advocates—who have found something to dislike in the bill.

In short, Congress remains stuck. As these pieces of legislation flounder in the courts or House, the question remains: what will Congress do to curb the risks of online harm and manipulation of our kids?

We need to act to protect child safety, to be sure. An additional benefit of such work: Congress needs to put its toe in the water on broader reforms of Section 230 that could help inform how we address the dissemination of harmful content, from bioterrorism to electoral manipulation and health disinformation. Rather than taking on the myriad of regulatory and legal issues that arise in those areas, I’ll suggest a general framework to address the urgency of the threat to our kids today, which might provide an approach for broader questions of content moderation.

Creating a “Safe Harbor”—And Pushing Irresponsible Companies into the Storm

Nothing motivates industry to change its behavior like a claim on its shareholders’ assets. That underlies one approach to compelling greater safety: let’s create clear lines that expose companies to liability for negligently putting our children in peril.

Congress could supplant Section 230’s broad exemption of social media platforms from liability with a statute that would create a “safe harbor” from all lawsuits for companies that meet or exceed the very best industry practices for protecting children. That is, we tell companies that they can avoid lawsuits by adopting those best practices. By failing to do so, they roll the dice. That is, their neglect gives rise to uncertain liability, but a certainty of legal bills.

The challenge lies in determining what behavior falls short of those best practices; that is, specifically defining what courts call the “standard of care.” In an industry with rapidly changing technology, Congress cannot establish a static threshold; rather, the standard must evolve as the industry discovers better mechanisms for features such as age verification or algorithmic safety.

An evolving industry standard can be established by an external, independent body of academic, legal, and industry experts, which might articulate an revised standard of care every six months. Those experts must have the requisite technological and business savvy to understand what can reasonably be demanded of the industry, but must also remain subject to conflict-of-interest restrictions to avoid “agency capture” by industry. The body should likely be non-governmental and private—in the same way that Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) sets standards for the accounting industry, for example—or perhaps quasi-public, with industry and government participation. Regardless, the oversight body would establish clear thresholds, defined by its view of the industry’s best practices for child safety.

The legislation must also resolve a threshold question: “Who has the right to sue?” Typically, Congress would identify a set of appropriate federal and state agencies, such as the Department of Justice or state attorneys general. Since those public agencies may lack sufficient resources to be vigilant in exercising that right, we should at least consider the possibility of creating a “private right of action” that empowers parents to be our cops—or at least our whistleblowers—where they have standing to sue.

Congress must also identify which “best practices” should comprise the industry standard of care. At a minimum, they should focus on a few of the following elements:

- Prohibit the “Screen Nicotine”

Child-safe regulations must eliminate those design features that make the use of the platform or app particularly addictive for young people—or what I call “screen nicotine.” Regulations would halt infinite feeds and autoplay, and mandate natural stopping points with tools that cap the amount of time children spend on the service, as technologist Tom Kemp urges in Containing Big Tech. It should prohibit push notifications and other mechanisms that draw young users back to their screens, and otherwise help parents break their kids’ compulsive use of social media and apps.

- Age Verification Standards

Haidt urges that children should not have access to social media before the age of 16. While reasonable minds can debate the optimal age threshold, some age verification is critical, particularly for platforms and apps likely to contain mature content. Congress should also assess whether there’s a role for app stores to take greater responsibility. Some industry experts have urged that App Store and Google Play should require any user under the age of 16 to receive parental approval to download any app.

The efficacy of age verification tools, of course, remains imperfect. Tech companies assert that they often cannot verify the age of a user seeking to evade age restrictions, and everyone knows a child (like my niece) who can tell them about how they got an Instagram account under the required age of 13. Nonetheless, “best practices” can encourage creative verification methods, such as using the verified ages of friends on social media platforms, or for younger kids, detecting the continuous streaming of Peppa or Yo Gabba Gabba for extended durations. These tools will also improve, and better “best practices” will emerge.

- Data Collection and Privacy

Again, much of this work begins with a data privacy bill. Congress enacted the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) in part to require apps targeting young audiences to use age verification tools before collecting any data from kids online. Yet a Washington Post investigation found that 67% of the 1,000 most common child-focused apps routinely shared personal data, including locational information, about young users with advertisers—often without seeking prior parental permission.[43] Once advertisers and data brokers have such information, children can be tracked across the web.

- Health and Sexuality

We must ensure that pre-teens have access to accurate health and medical information (e.g., verified by studies in credible peer-reviewed journals) that helps them better understand personal issues about gender, sexuality, and health about which they might feel uncomfortable discussing with an adult. More than a few of my LGBTQ friends and children of friends have benefited enormously from online access to such information.

- It Takes a Village to Keep Our Kids Safe: Beyond the Companies’ Role

Congress might reinforce the efforts of local and state governments to reinforce a healthier life-screen time balance, such as by incentivizing school districts to ban cell phones during school hours. Congress can empower law enforcement and prosecutors to stop and deter predatory behavior, as we see in several pending bills, such as Senator Amy Klobuchar’s SHIELD Act.

We can better empower parents—such as by establishing clear “ratings systems” to assess the safety of specific platforms and apps, as we saw decades ago in the film industry—to ensure they can properly exercise their own responsibility over their kids’ screen use.

Finally, we can better educate our kids. For example, New York Times columnist (and more notably, Hard Fork Delphic oracle) Kevin Roose suggests that we require companies to mandate that underage users complete a standardized online tutorial—complete with a quiz—to help them understand the perils of online use. Whether or not such a practice currently constitutes a best practice, it probably should.

Regulating Cryptocurrency: Sensible First Steps

While Congress has dithered, the crypto industry has exploded—and occasionally imploded—largely without any sensible regulatory framework from Congress. The $2.3 trillion digital asset genie is now very much out of the bottle, and the clock is ticking. The SEC has begun to approve several Bitcoin exchange-traded funds (ETFs), widening access to tens of millions of retail investors of widely varying sophistication levels.[44] The current legislative void has spurred the courts and regulators to jump in, tethering legal theories to outmoded laws with inconsistent outcomes. Congressional action is long overdue.

What is the cost of inaction? The industry is increasingly moving (and hiring) offshore to nations that provide more regulatory certainty. Before wary observers say good riddance, consider that a relatively unregulated, fast-growing fintech industry moving to foreign countries leaves us with the worst of both worlds. That is, American retail investors and consumers face a much greater risk of being duped in a “wild west” regulatory environment, putting bad actors beyond the reach of U.S. authorities and enforcement. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy loses job opportunities and cedes growth abroad.

We need sensible regulation—laws that mandate transparency, accountability, and safety for the tens of millions of Americans who appear increasingly willing to tread into this uncertain landscape. We also need rules that affirm and support technology that can provide a democratizing influence on public finance.

Here are a few logical first steps Congress can take on crypto to bring regulatory certainty to an industry that is clearly here to stay.

Start with Stablecoin

Stablecoin is designed to maintain its value by pegging its price to a stable asset like a fiat currency, such as the U.S. dollar, or to a commodity like gold. Due to its relative price stability, stablecoin offers a better mechanism for payments than more volatile cryptocurrencies like bitcoin.[45] Stablecoins that digitize the dollar—like USDC and TrueUSD—could provide a long-term advantage to the U.S. economy. Having the world’s principal reserve currency over the last 80 years has provided massive advantages to American businesses, consumers, and our government, enabling us to borrow at a lower cost and making U.S. sanctions more impactful. As crypto becomes more prominent in remittances to family members living abroad, it is important that those transactions occur in dollars.

While regulating stablecoin seems elementary for many in the industry, fears have emerged on Capitol Hill and elsewhere. Some have warned of “Big Brother” tracking every consumer’s expenditure. Yet, relatively standard regulatory measures could adequately protect privacy. Fears of expanding the money supply are mitigated by ensuring that every stablecoin is redeemable with a collateral reserve asset (although some stablecoin use algorithmic formulas, which are supposed to control supply). Obviously, that requires governmental oversight.

The primary obstacle in Congress appears to be the role of states. Some states, such as New York, insist on maintaining regulatory authority, which creates a troubling thicket of regulatory compliance for any company seeking to have its cryptocurrency seamlessly relied upon throughout the world. There is a strong case for federal preemption here, to ensure a uniform set of rules—and consumer protections—across 50 states.

Nonetheless, legislation to regulate stablecoin has languished for a couple of sessions, despite relatively bipartisan support. Digitizing currency can provide an early toe-in-the-water opportunity for Congress and federal regulators. Distributed ledgers created by blockchain technology may offer effective means to digitize stock ownership, government-issued identification, and other instruments of daily life. It’s time for Congress to act.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All: Defining Regulatory Scope

Legislation to assign jurisdiction to federal agencies on cryptocurrency, commonly known as a market structure bill, emerged from committee in 2023. Until Congress passes legislation clearly defining who regulates what, agencies will trip over each other while competing for turf. Congress must also determine whether the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) has the resources to resolve how to apply 90-year-old securities laws within the crypto ecosystem. The complexity of these questions appears exacerbated by the fact that securities laws, which generally mandate the presence of intermediaries, are a poor fit for crypto, which is defined by its decentralization and disintermediation.

Under longstanding federal law and Supreme Court precedent, the SEC should regulate cryptocurrency only where it constitutes an “investment contract.” Nobody claims that currencies such as the peso or euro constitute an investment contract, because we use international currency markets to facilitate international transactions for goods and services, not to provide returns. Many experts believe that crypto tokens function more like commodities than investment contracts, and that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) constitutes the logical entity for regulating cryptocurrency like Bitcoin and Ether, not the SEC.

Where companies purport to bundle tokens with opportunities for return beyond the currency’s mere fluctuation in price, the cryptocurrency should be treated like an investment contract by the SEC. An example includes Blockchain Capital’s B-CAP, in which investors expect (or hope for) some rate of return for their purchase. Form—and regulation—should follow function.

In summary, when tokens change hands without any connection to an investment contract, they should not be regulated as securities. Too often, we’ve seen the regulatory agencies fail to draw logical lines. For example, the Blockchain Association notes that “the SEC has refused to approve applications from registered securities exchanges to list a spot bitcoin exchange-traded product (ETP) despite approving bitcoin futures ETPs.”[46] The SEC’s recent overreach in the case against Ripple was ultimately rejected by a federal court—after years of litigation, substantial cost, and market disruption. Astoundingly, federal courts are left to decide about the SEC’s role by resorting to a standard established by a nearly 80-year-old Supreme Court decision, SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., from 1946.

That’s not reassuring. Congress must draw clear lines here—define the turf and accompanying rules to provide some predictability and consistency in crypto regulation. Congress should also heed the call of Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to close the gaps in regulation. Spot commodities like Bitcoin remain largely unregulated, and Congress must close these gaps while ensuring a coherent regulatory regime for all cryptocurrency.

A Safer “Sandbox”

Finally, there’s little question that cryptocurrency investment poses substantial risks for any retail investor, as evidenced by the wild volatility of currencies like Bitcoin in recent years. To be sure, consumers and retail investors must enter these markets with eyes wide open, but regulatory agencies have a role to ensure transparency—if Congress will clearly authorize them to do so. Some experts have advocated for the creation of a regulatory “sandbox” for retail investors and consumers, within which tokens can only be traded where their crypto sponsors meet very high standards of disclosure and transparency. The establishment of clear rules for the identification of the actual parties engaging in the market—often referred to as “white list systems” for financial institutions—can ensure legitimacy of the transactions and deter participation by criminal organizations. Legislation to create such a regulatory sandbox has languished in Congress.

Working with regulatory agencies and industry, Congress must move. Let’s get it done.

INVESTMENT IN INNOVATION: KEEPING THE GOLDEN EGGS AND THE GOOSE

Tax Treatment of Research and Development Expenditures

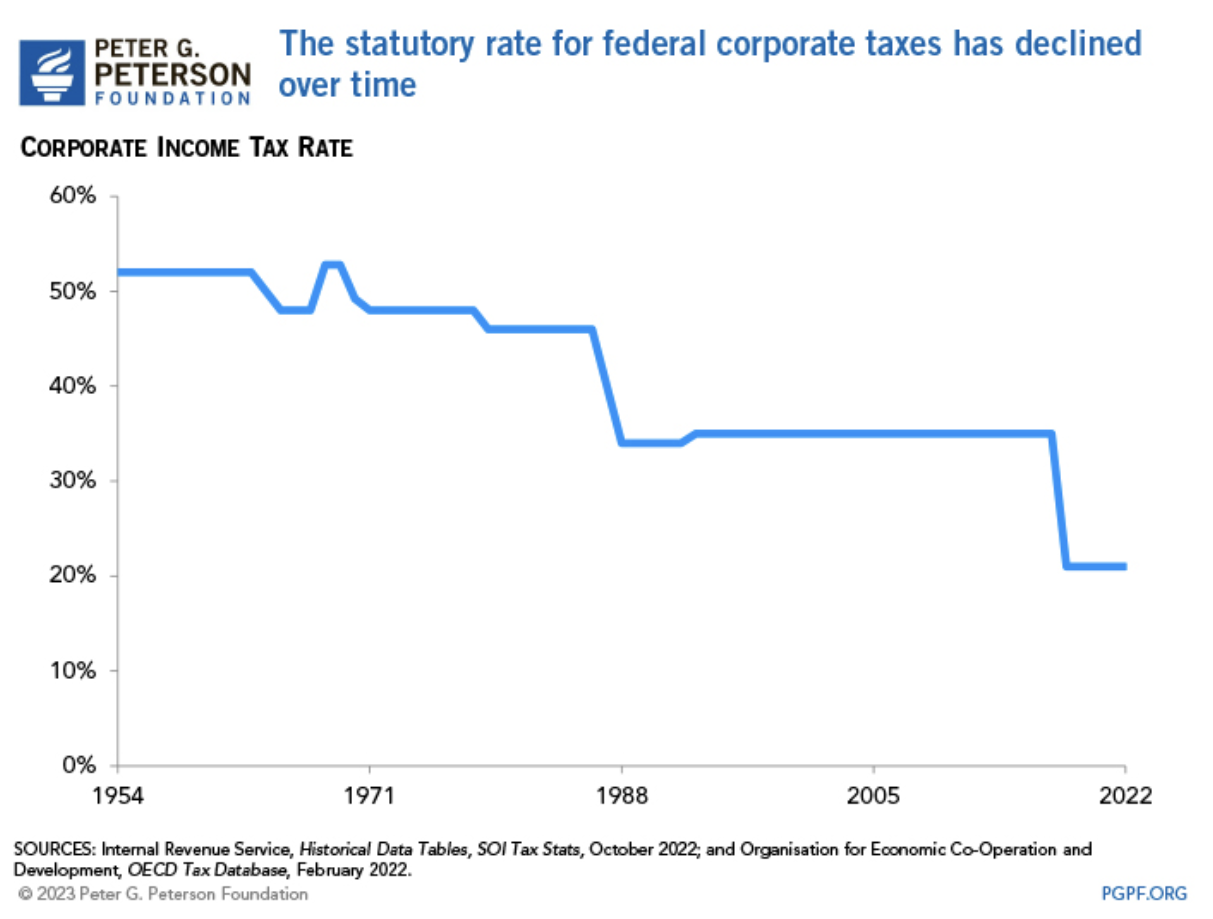

Many of the provisions in the Trump tax bill of 2017—more formally known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—will expire in 2025, and tax policy will move to center stage. With an estimated $1.9 trillion deficit in the coming year, many experts believe that tax increases will be on the table—specifically, the 21% marginal tax rate on corporate income. This illustration from the Peterson Foundation, a nonpartisan budgetary think tank, demonstrates the historically low marginal rates enjoyed by many corporations since the 2017 law took effect:

Yet the marginal rate tells only a small part of the story. While the media and public focus on the marginal rate, the “action” in tax policy is typically in the complex maze of deductions and tax credits negotiated in each tax bill. As a result, the actual tax paid by corporations is far less—the 2017 law reduced the effective tax for large corporations to 9% in 2018, down from 14% in 2014.[47]

The parties will disagree about whether to increase that marginal rate, but they should agree that it is critical for our long-term economic viability to restore the deduction for research and development spending.

As we consider our collective future, research constitutes the most important dimension of the Valley’s private sector activity. Our world critically needs innovative people and path-breaking firms to discover the next cancer drug, better ways to store and deliver electricity, and less costly means of providing clean drinking water. Discovery drives our economic growth and high quality of life, and–as we consider climate change or pandemics–will be essential for our survival. Ample studies show how research and development activity of the private sector produces social benefits to many others in the economy—particularly consumers—that far exceed the private benefits to the firm.

Yet it’s far from certain that any company will secure the “golden eggs” of research and development. The risks of R & D investment are great. While individual early-stage Valley companies routinely perish, the “goose” of research and development investment must survive for our economy to flourish, that is, to have any golden eggs in the future.

The many costs of research—in the form of clinical trials, scientist and engineer salaries, laboratory equipment, and patent applications—constitutes a multibillion-dollar line item on the balance sheet of many large companies, and consumes a disproportionately large share of capital for small startups. In many fields, the high cost, remote payoffs, and heavy risk of research and development makes it infeasible if financed purely through market mechanisms.

Federal tax policy can promote long-term economic growth by incentivizing research and development. In competing nations such as China, companies with sizable research expenditures do not merely receive tax breaks, but massive subsidies—outright infusions of capital, free land, and the like.[48]

The Trump “tax cut” law has ironically penalized investment in research and development. Since 1954, the tax code has allowed companies to deduct 100% of the firm’s expenses—employee salaries, benefits, lab space, and the like—in the year in which those expenses are incurred. That is the rule in nearly every other OECD country as well.[49] Yet since 2022, the deductibility of research and experimental expenses under Section 174 must be amortized over five years if incurred in the U.S. (and 15 years if conducted abroad). In other words, companies can deduct less than 20% of the cost of a scientist’s or software engineer’s salary, benefits, and overhead in the current year, but it can still deduct 100% of the cost of hiring a receptionist, marketing staff, or an administrative vice president.

The incentives are all wrong. American companies are still spending, but U.S. research and development investment in 2023 was outpaced 5:1 by other business expenses in 2023.[50] That’s the opposite of what we need to ensure American economic competitiveness.

Although some U.S. businesses may avail themselves of a tax credit that the Code makes available for some research and development expenditures, companies cannot use both a credit and deduction for the same expenditures. The tax credit is limited in scope and application, and its complexity leaves most small businesses beyond its reach, even if they qualify.

The new mandate to amortize research and development expenses has already resulted in the loss of jobs and investment; employers have cut 14,000 research and development jobs since the imposition of the new rules.[51] The growth rate of research and development spending has slowed from 6.6 percent annually from 2017–22 to less than one-half percent in 2023.

Who bears the burden for this? Small tech and innovation companies—which tend to drive a disproportionate share of our innovation—feel the pinch sharply, because they devote the largest share of their budgets to research and development. Big Tech tends not to be as affected, nor do startups that are not yet profitable, but small and mid-size companies clearly take the hit.

We need to fix this mistake. Several bills have been introduced to restore full immediate deductibility of research and development expenditures, and revert Section 174 to its pre-2022 status. So far, none have gotten over the goal line, but 2025 will be the critical year for deliberation, with multiple high-profile tax provisions set to expire.

Of course, we have a serious deficit, and fast-growing national debt. We must manage these tax expenditures responsibly, without aggravating the rate at which we’re saddling our children and grandchildren with federal debt. How do we pay for the roughly $20 billion reduction in revenue that will result from restoring the full deductibility of research and development spending?[52]

Congress has several options, but I suggest looking at a couple to start. First we can nudge the 21% marginal tax rate on corporations upward, closer to its historic average. It’s at a historic low, resulting in an effective tax rate of only 9% for a corporation with at least $10 million in assets. An increase of 2% in the marginal corporate rate would generate approximately $22 billion, sufficient to backfill the foregone revenue.[53] Under my proposal, innovative companies that focus on research and development would pay less, while more conventional corporations would pay more.

Alternatively, Congress could also pay for research and development deductibility by reforming loopholes in the Qualified Business Income deduction, a creature of the 2017 tax law that Federal Reserve economists have found has induced billions in tax-avoidance and recharacterization of income without any inducement of new investment, jobs, or any other obvious economic benefit. That is, Congress could simply raise the rate by a commensurate amount on large-revenue limited partnerships, S corporations, and other pass-through entities that many high-income investors use to reduce tax bills. While real estate investment trusts and other investment vehicles received very generous treatment in the 2017 Trump tax changes, R&D-focused early stage companies suffered.

Any economist will readily urge more favorable tax treatment for a company designing the next-generation energy storage device over a company investing in shopping centers. Congress should listen to our economists.

Investment in Basic Science and Research

To speak to a Silicon Valley audience in favor of investment in basic science and research lies somewhere between pandering and preaching to the choir. Suffice to say, I strongly support more federal investment in basic science and research. As mayor of Silicon Valley’s largest city, I’ve lobbied for funding for NIH, NIS, ARPA-E, ARPA-H, and other critical priorities on Capitol Hill, standing alongside leaders of our top universities and research institutions, and with CEO’s of local companies. We need federal investment.

Private R& D investment is a good thing, to be sure, but it’s different. It’s focused on commercialization– bringing products and services to market. It can have widespread benefits, but it doesn’t have to, and the profits of proprietary technology are inherently exclusive. Those technologies can also produce widespread harm as well; consider the development of Agent Orange, for example.

Private corporations have little incentive to invest in basic, “open source” research–the very kind upon which much of our technological, scientific, and economic progress depends. Without Einstein’s 1905 discovery that gravitational forces affect the rate of passage of time, for example, modern GPS technology would produce distorted outcomes today.

We critically need investment in R&D that takes the “long view.” Industry will appropriately conduct research where focused on getting a product out to market, but the benefits of basic scientific research remain too diffuse to attract sufficient private capital, beyond philanthropic sources for technology that is far from any commercial viability. Today,

the federal government remains the nation’s largest supporter of basic research, funding 40.0% of U.S. basic research in 2021, with universities, state governments, and other nonprofit organizations funding another 23 percent.

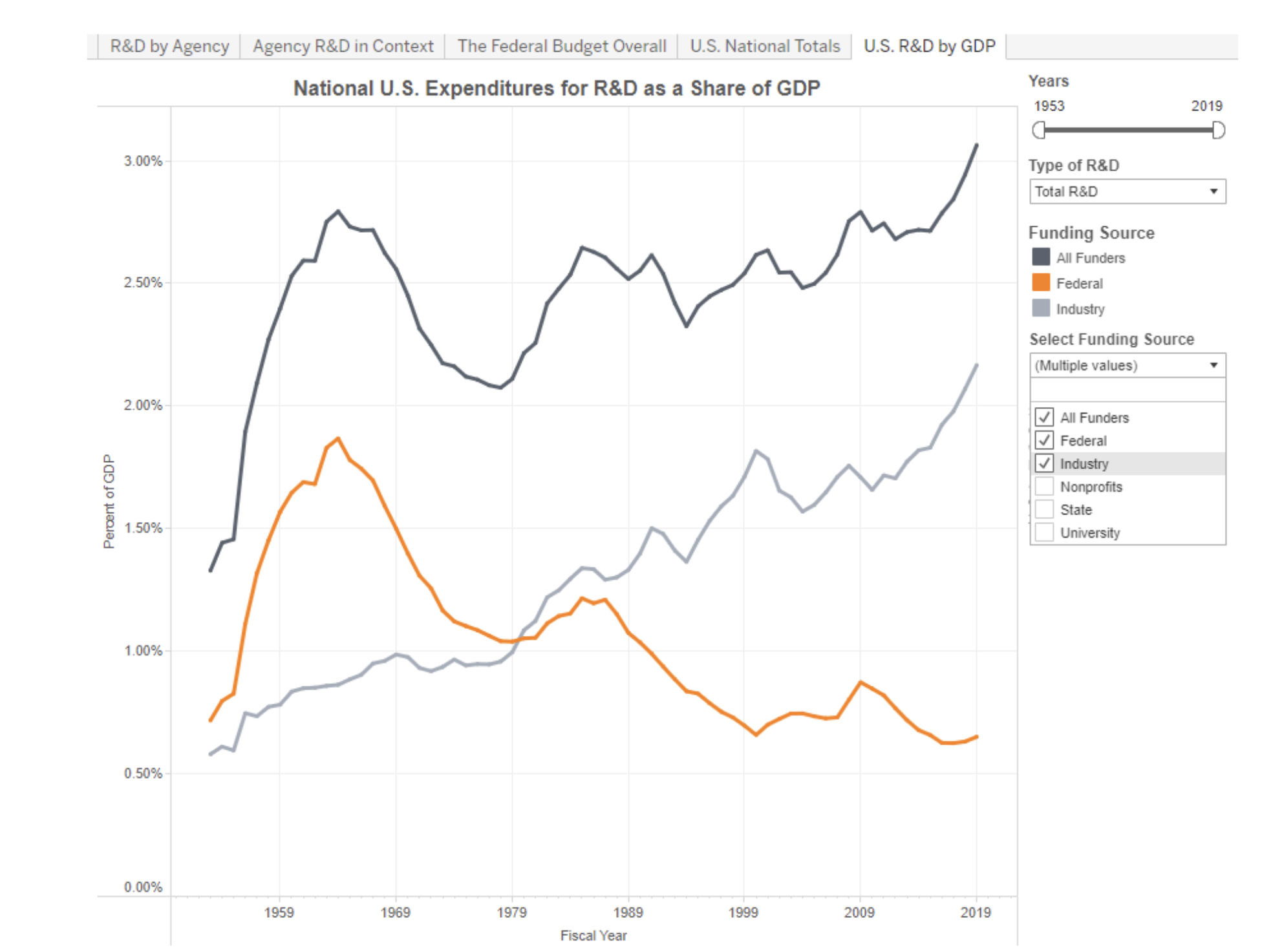

While China, India, and the EU nations such as Germany continue to accelerate public investments in research and investment, U.S. federal investment in research and development has declined relative to the size of our economy, as this graph reveals:

The decline appears even more stark if funding from the national Institutes of Health is excluded. Assuming that we agree that we need more federal investment in basic scientific research, the

real question, is how do we pay for it?

I’d start with corporate subsidies.

I’m generally not a fan of what’s known as “industrial policy”– the favoring of specific industries and companies with direct subsidies, tax breaks, import duties, trade barriers, and other fruits of government benefice. Companies generally shouldn’t get taxpayer-funded support or exemptions.

Many politicians on both sides of the aisle will disagree with me, however. Industrial policy has been on the rise in the U.S. and throughout the industrialized world, particularly since the pandemic. It seems to be one of the rare areas of bipartisan consensus–if the parties could just agree on which industries to subsidize. So, they logroll, and virtually every industry, from agriculture to aerospace, receives favorted industrial policy treatment, and increasingly so.

Most mainstream economists share my dim view of industrial policy, because taxpayer investments in industry tend to do better for industry than for taxpayers. Governments–least of all, Congress–aren’t good at picking the winners and losers in the market. “Industry capture” ensures that subsidies last well beyond the duration of their utility, if they’re needed at all. Direct subsidies and tax expenditures continue to bloat our federal budget to leaden the debt–now exceeding $35 trillion– burdening our children. Repeated studies show that the economic gains to workers of industrial policy subsidies and trade restrictions would have come at a lower cost if we’d just distributed cash to each worker. Distortions disrupt markets and economies with excessive government intervention. They create obstacles that that often inhibit newer, more innovative firms from succeeding where the market would allow them to. As David Brooks recently observed, “The International Monetary Fund and Global Trade Alert monitored over 2,500 industrial policies around the world last year and found that more than two-thirds distorted trade, discriminating against foreign concerns. Furthermore, this kind of protectionism backfires. More workers lose their jobs when other countries retaliate than gain jobs from the protections themselves.”

I will admit to exceptions to my condemnation of industrial policy. Undoubtedly, unique and urgent cases require government intervention, for national security, mitigation of climate change, or critical supply chain resilience. One such instance arose with the passage of the CHIPs and Science Act, which appears to have had success in spurring development, though not without hiccups. Yet there are plenty of subsidies that most of us would readily agree serve no public benefit, such as the tens of billions in annual tax exemptions, credits, and deductions for the oil and gas industry.

Let’s reallocate many of the subsidies to industry toward greater investment in basic science and research, through our national laboratories and research universities. The R&D may well benefit the very same industries, but it will do so in less distortive ways to the overall economy, and it will produce public gains – in advancing science and knowledge– that will benefit people more broadly.

Will this be difficult politically? Brutally. Everyone has a favorite industry subsidy to cling to, and as the saying goes, in “where you stand depends on where you sit.” Representatives of Kansas will defend agricultural subsidies just as Oklahoma members protect oil drilling subsidies. There’s no magic solution here, and these subsidies won’t go away without a fight.

But we should agree on where to start, and that’s where I’d start.

“The Exit”: Innovation and Antitrust Enforcement

Serious risks threaten our economy and society from excessive concentration of technological prowess. We need robust antitrust enforcement in many sectors of our economy to protect consumers, ensure opportunity for start-ups, and to maintain the competition that fuels America’s economic success.

Yet in my conversations with leading innovators in the Valley, a surprisingly large number of startup founders and venture funders in life sciences identify antitrust enforcement as a substantial barrier to their company’s—and their industry’s—growth. To be clear, these innovators have no interest in shilling for tech behemoths like Apple or Amazon, nor for large health care conglomerates like United Healthcare or CVS Health. None of them face a direct risk of incurring the wrath of regulators at the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or of litigators at the Department of Justice. Rather, their concern about antitrust focuses on preserving the essential catalyst to investment in medical innovation: “the exit.”

The Exit

To many, “the exit” embodies the ambition of every shopaholic’s spouse stuck in a mall on a Saturday afternoon. To founders and venture capitalists, it means much more. Traditional lending is not available to high-risk, early-stage tech companies. Rather, start-ups seeking the capital necessary to grow have two primary paths: “going public,” and acquisition. A company goes public by making its stock available to public investors through an initial public offering (IPO) or by acquisition by a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). Venture capitalists invest their dollars in early-stage companies with the expectation (or more frequently, with the unrequited aspiration) that the exit will enable them to recover their investment and earn a healthy return.

Here’s the rub: the investment decision depends on the market’s perception of each startup’s likelihood of exit. Without the prospect of an exit, a venture capital firm loses any incentive to invest.

The traditional exit path—going public—has become increasingly disfavored, for a variety of reasons. The passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and its accompanying regulations have imposed rigorous reporting requirements on public companies that many executives view as excessively burdensome and litigation-inducing. Moreover, IPOs don’t fit in the vision of many company founders. Many founders believe that becoming a publicly-traded company—and the accompanying imperative to demonstrate growing profitability each quarter—will undermine their long-term growth and technology development. For many life science startups, the markets will never embrace a “one-trick pony” firm that focuses on the development of a single molecule or medical device, so they can only get access to capital through acquisition. In short, the limitations of “going public” leaves many early-stage companies with only one path: acquisition.

Why are these early-stage companies so important? More than in other industries, the medical devices, cancer treatments, and other breakthroughs in the life sciences result from the endeavors of early-stage companies, sometimes in partnership with research universities and institutes. An astounding concentration of that ground-breaking research occurs within a couple miles of the 101 corridor between South San Francisco and San Jose. Startups appear more nimble, more willing to take risks, and more attractive to hard-charging innovators.

Yet venture capital gets these early-stage life science innovators only so far. A single clinical trial for a drug seeking FDA approval can cost tens or hundreds of millions, depending on the complexity of testing required.[54] In most cases, drugs fail to meet the FDA’s appropriately robust standards for efficacy and safety. Those failures cost more money.

All told, it can cost as much as two to three billion dollars to bring a blockbuster drug to market. Big Pharma and major healthcare conglomerates provide the much larger capital to startups to pay for costly clinical testing, lab equipment, and manufacturing facilities. Without an ecosystem that allows for acquisition, these smaller companies, and their life-saving innovations, wither on the vine.

Here’s the problem: aggressive antitrust enforcement by the FTC increasingly discourages venture investment in early-stage, innovative companies, particularly in the life sciences. While we have not seen a substantial fallout in investment, we have seen a shift of funding away from early-stage companies toward safer bets.[55] Many warn that the spigot for funding startups could slow, because current FTC activity threatens the innovation ecosystem.

Of course, we have no reason to worry about the well-being of venture capitalists—they’ll find other places to put their money. We should care, though, if this trend impedes the industry’s ability to produce the next critical vaccine, breast cancer treatment, or Alzheimers’ drug. We should also care if some large companies increasingly use counterproductive tactics to evade antitrust review, such as acquiring the technology and top talent of smaller companies, while leaving most of their employees—and the carcass of the company—behind.[56]

The Necessity and Perils of Antitrust Enforcement

To be clear: we need robust antitrust enforcement. We need to protect consumers from monopolistic pricing that exacerbates our high cost of living. We need to enable the competitive forces that drive innovation and economic growth. That requires the vigilance of the FTC and Justice Department for anti-competitive behavior by corporate behemoths. I’ve urged for greater enforcement in my book in areas such as grocery consolidation and pharmaceutical distribution.

In tech, one can find ample examples of problematic behavior. The recent civil complaint against Amazon, for example, appropriately focuses on the online retailer’s requirement that any company selling on its platform cannot offer a lower price on a competing platform.[57] Consumers suffer harm when deprived of competitive pricing. So long as FTC uses the same standard to enforce conduct by the nation’s largest retailer, Walmart, as it does against Amazon, we should cheer the FTC and its Chairperson, Lina Khan.

The problem lies in those instances where the FTC cuts such a broad swath that it leaves many in the industry unclear about what is or is not unlawful. The FTC has lost every single merger challenge that it has brought in court and in administrative proceedings, ranging from Microsoft to Meta to Illumina. The agency has relied upon novel legal theories that generally exceed the bounds of accepted jurisprudence. Even in cases that never reach an administrative or judicial decision, several efforts to halt or stall mergers left industry observers scratching their heads. For example, the FTC’s efforts to block Amgen’s purchase of Horizon Therapeutics surprised industry analysts because the companies don’t have any competing products, and had even Amgen’s competitors rallying to its defense.[58]

“Surprise” enforcement doesn’t serve anyone. Corporate leadership and their employees should have clear rules about what is legal and what is not. Even when they prevail against the FTC in court, employers incur millions in litigation costs, and much more from delay. A ripple effect across the industry hamstrings companies from standard licensing or acquisition deals because of regulatory risk and legal uncertainty. That uncertainty chills investment in many early-stage companies with promising technologies, according to many Valley veterans.

Drawing Clearer Lines

It has become vogue to fault Chairperson Khan for overly aggressive antitrust enforcement. In my view, the blame also lies at the door of Congress. Congress makes laws. The key statutes defining prohibited conduct—the Sherman Antitrust Act, Clayton Act, and the Federal Trade Commission Act—have remained largely unchanged for nearly a century. Consider the multitude of new industries that have emerged and developed over that duration: trucking, airlines, telephone, pharmaceuticals, television and film, telecommunications, computers, computer software, online commerce, electronic gaming, social media, and AI. The law has failed to evolve with our economy, and many blurry lines need to be made clear.