Read Sam's book

Homelessness

Why Homelessness Isn’t Merely a

“Local Issue”

In my many hours walking the halls of Congress, whenever I advocated for greater attention to homelessness—such as expanding rent limits on Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing vouchers to help homeless veterans get off the street—I routinely was told, “that’s a local issue.”

The data tells us otherwise. 44 of America’s largest 48 cities have at least 1,000 unhoused residents.[1] Homelessness jumped 12% nationally in the last year alone, and on any given night, 653,000 Americans remain unhoused.[2]

Homelessness is an important “local” issue in virtually every major metropolitan area, from Miami to Anchorage. In other words, it’s a national issue. It’s just that we haven’t seen any significant policy action by Congress in recent memory to address homelessness. Plenty of observers have reasonably asked, “If my city and county are spending all of these resources on homelessness, why isn’t the federal government doing more?”

Here are a few ways that I believe Congress can make a difference, both for homelessness and the related issues of addiction and mental health:

- Building Housing Faster and at a Lower Cost

- Leveraging the Power of Housing Vouchers

- Financing Affordable Construction More Nimbly

- An Ounce of Prevention Can Save a Pound of Misery

- Eliminating Barriers to Treatment of Addiction and Mental Illness

1. Building Housing Faster and at a Lower Cost

Two years ago, I had the pleasure of meeting Ludia. She and her grandsons had been living in and out of shelters for several months and could not find an available apartment where the landlord would accept her housing voucher. She was relieved to finally land at a recently-opened transitional housing community for families, on Evans Lane in West San José.[3] She told me that her family enjoyed having a small apartment of their own, with the privacy of her own bathroom, a space in the community garden to grow vegetables, a large community kitchen, and a computer lab where her grandsons could do their homework.

Ludia kept looking for permanent housing, with the assistance of a case worker at Evans Lane. Although it took her more than a year to find a landlord in San José who would accept her voucher, she stuck through it and is now living on her own in West San José.

The traditional approach to building housing isn’t cheap—constructing an “affordable” apartment building in our area will cost about $938,700 per unit—and it takes five or six years of planning, city approvals, financing, construction, and inspections before anyone can occupy it.[4] We can’t tackle a crisis that afflicts our 12,000 unhoused residents in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties that way. We need to be much more nimble.

During my mayoral tenure, we worked to find innovative approaches that could help us expand the housing supply faster and less expensively. We began converting two motels into housing in 2016, about four years before Governor Gavin Newsom implemented this approach statewide.

We partnered with Habitat for Humanity to build “tiny home” communities on two sites in 2017, at first with only modest success. With every iteration, we learned, reassessed, and pivoted.

In March 2020, under state orders to vacate our shelters to protect unhoused residents from COVID, I put the challenge to our public works team at the city: How quickly could we build small communities of prefabricated, modular dorms—with private bedrooms and bathrooms—on public land? We had about $17 million in funds to work with, and I committed to raising money philanthropically. Our team responded—as did Susanna and Peter Pau and Sue and John Sobrato, two generous couples who donated several millions of dollars. We built three “quick-build” communities housing 300 residents in a matter of months, not years.[5] The cost? Less than $110,000 per unit, rather than the conventional $938,700 per unit.[6]

Unlike “tiny homes” and “tuff sheds,” these dorms provide residents with private bedrooms and bathrooms, utilities, hot water, a safe lock on their door, and space for their pets and belongings. These features are not mere conveniences; they’re essential to persuade many unhoused residents to leave the streets, who often fear that traditional shelters will fail to offer safety, privacy, dignity, or space. City-funded non-profits provided mental health counseling and programs to residents grappling with the trauma they experienced on the streets, as well as helping them to find jobs.

To bring people off the streets, we need to create places people will actually choose to go. Federal courts will make it very difficult on cities who merely want to push people off the streets involuntarily. Consent always yields better outcomes. That’s how Ludia became one of our many success stories.

Soon other cities, such as Mountain View and Redwood City, launched prefabricated communities of their own with their own variations on the model.[7] We benefited from learning from each other, and the idea began to scale. Cities typically used these models for transitional housing—places to stay for several months until permanent housing could be identified. Later iterations of San Jose’s prefabricated communities, however, were built to federal standards with small kitchens to use flexibly as permanent housing as well.

By the time I left office at the end of 2022, San José had constructed five quick-build housing communities. It would take time for us to see the outcomes from our work, but I was proud that my successor, Mayor Matt Mahan, could announce the results: unsheltered homelessness dropped nearly 11% in 2022.[8] In the rest of Santa Clara County, homelessness increased.

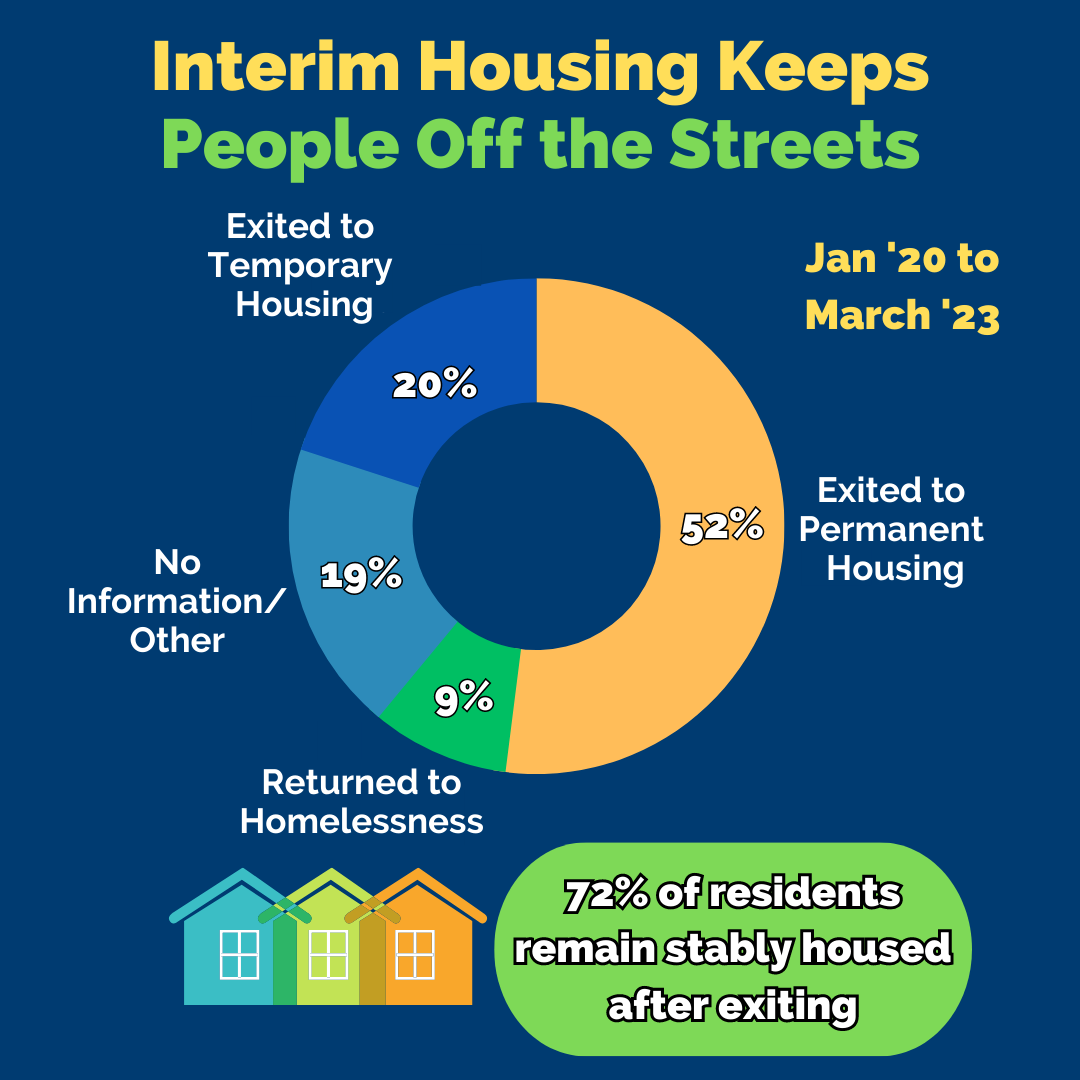

Critically, the outcomes for residents also appear promising. In congregate shelters and navigation centers, most of the people return to the street and typically fewer than 20% of residents land in permanent housing. In our interim quick-build communities, more than 72% remained housed more than two years later, most of whom found permanent housing.[9]

Our solution used what’s called “factory-built housing,” which has taken off, and so has demand. Several years ago, the Northern California Carpenters Union perceptively began partnering with startups like FactoryOS to see how we could accelerate construction at a lower cost, while still maintaining fair union wages.

With growing demand has come challenges. Costs of prefabricated units have increased dramatically since we started in 2020; supply chain challenges stalled projects throughout the pandemic. In some cases, poor construction quality undermined success. Enabling better, more cost-effective prefabricated quick-build construction is critical to getting the 653,000 unhoused Americans off the streets and into dignified housing more quickly.

Congress must step up, particularly in helping this nascent industry to scale to better meet the need. Financing new factories has been a challenge for some small companies, particularly given the uncertain demand. Congress can use the government’s purchasing power, within the existing authorized budget for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), to create a steady demand that many factories need to expand. It can establish minimum standards for construction for eligibility for federal funding, and certify suppliers that meet quality criteria to make it easier for cities and counties that want to find quality builders. It can support efforts, like those of the Carpenters Union, to expand workforce training for well-paying jobs in factory-built housing in areas suffering from high unemployment. It can help modular builders satisfy bonding requirements and other requirements associated with conventional construction.[10]

Importantly, Congress can also eliminate statutory restrictions on the use of federal housing choice vouchers for transitional housing units. Federal law allows vouchers to be deployed in units that cost $1 million to build, but not in units that cost $150,000. If cities like San Jose, Mountain View, and Redwood City could accept payment by federal vouchers for their transitional communities, it would help those cities pay for the operations of these communities and clear a path to build more of them. Residents could stay in a transitional community for several months, and when an apartment elsewhere opens, they could take their voucher with them. To get there, we need changes in the law governing vouchers, which we’ll turn to next.

2. Leveraging the Power of Housing Vouchers

Since the demise of federally-funded public housing in the 1970s, the majority of federal rental assistance comes through housing vouchers, for people to use in the private market. About 2.35 million extremely low-income families now use housing choice vouchers to stay housed.[11] Often referred to by such programmatic names as “Section 8” or “VASH,” vouchers constitute the most effective federal housing program along several key metrics—for reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding.[12]

How do vouchers work? Each household must contribute 30 percent of its income, and the voucher covers the rest of the costs of rent and utilities, up to a limit based on HUD’s fair market rent estimates. Families with vouchers have the ability to choose where they live, with private landlords receiving most of the voucher revenue.

Vouchers had traditionally been seen as a less bureaucratic approach than the troubled legacy of public housing. Voucher holders had choices about where they would live, rather than facing confinement to deteriorating, government-owned housing projects. Great Society Democrats increasingly embraced the program, and it became a bipartisan program.[13] Despite the many flaws of the program—and there are flaws—it has generally survived because of something resembling a political consensus.

The biggest challenge is that voucher demand vastly outstrips supply. Only one out of every four families that qualify for vouchers actually get them. In October 2023, the San Francisco Housing Authority opened the waitlist for the first time in nearly a decade, and about 60,000 families signed up—for only 6,500 spots on the waitlist.[14] To be clear, every family had a one-in-ten chance of even making it onto the waitlist, and even then, the “winning” family or individual waits for years before actually receiving a voucher.

And what do these lucky sweepstakes winners get? Not enough of them get housed, unfortunately. Too many vouchers are held by people who can’t use them. In high-cost areas like ours, voucher holders can’t afford security deposits, application fees, or broker fees to get into apartments. Some landlords, frustrated by the bureaucracy of the system, refuse to accept vouchers, particularly where they have had the experience of leaving apartments vacant for two or three months while they await an inspection or approval from a federal HUD official. Many housing authorities require reassigning vouchers if a client doesn’t use theirs within a specified duration.

So, how can we better use vouchers to get more homeless Americans housed?

More Flexibility

Congress needs to make vouchers more flexible. Under the existing statute, public agencies can’t use a voucher for transitional housing. Making that simple change would enable more voucher holders to get off the street until permanent housing becomes available. So long as the transitional facility meets basic standards—providing basic utilities, private bathrooms, lockable bedrooms, etc.—it should be incorporated as part of a federal strategy to move more voucher holders off the streets. It would also help cash-strapped cities sustain and create more of this low-barrier housing.

For example, after the construction of San Jose’s quick-build transitional communities, we had to use city funding to provide supportive services like substance use counseling because Santa Clara County would not do so. (Counties receive all of the state and federal money to administer health programs in California; if counties refuse to provide mental health or addiction treatment, then cities need to dig into their own pockets.) Those services and operations can cost a typical city in the Bay Area roughly $35,000 per person. If residents had the ability to use vouchers at the transitional housing sites, the city could rely on a stream of federal money to support some of the operations and services of the communities.

A spirit of flexibility could also enable Congress to better incentivize landlords to accept vouchers—for example, by mandating provisional approval of a unit with an “inspection pending” where delays exceed a couple of weeks. Streamlining can help as well, as the current “balkanized and inefficient voucher delivery system” consists of thousands of public housing authorities, often with multiple agencies serving the same regional market, creating conflicting mandates and confusion for landlords and tenants.[15]

More flexible rules would make it easier on tenants as well: loosening the “use-it-or-lose-it” mandates to provide them more time to find apartments in tight housing markets, and enabling vouchers to cover the cost of security deposits. Providing greater flexibility on rent caps will also enable tenants to have greater opportunity to move to safer neighborhoods with better schools and resources—an important but often unrealized objective of the program.[16]

More Vouchers

“Better vouchers” is good. “More vouchers” is better. We simply need more vouchers. That’s not rocket science; four times as many families need them as have them.

Obviously, it will cost more money. With nearly every one of my proposed solutions, I’ve pulled back from ideas that simply spend more federal money. Our nation’s deficit is bloated enough, and our children don’t deserve more debt that we’re already giving them.

This issue is one in which I make an exception. We need more vouchers. A lot more of them. I cannot imagine a federal expenditure that could do more to reduce human misery. Many experts believe that the most direct, effective way to reduce homelessness lies in expanding the number of vouchers available to extremely low-income families—and they’re right.[17]

How much will it cost? Last year, the federal government spent $30 billion on vouchers.[18] Those 2.2 million households comprise only one-quarter of the total number of families who qualify for assistance. Some context: the federal government allots more than $95 billion annually in tax expenditures to homeowners, through such deductions as mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and capital gains on sale.[19]

While I’m a grateful homeowner, it’s hard not to see the inequity in that. If we spent even half as much on rental support as we spend on homeowners, we could serve more than another one million families in need, lifting them from abject poverty.

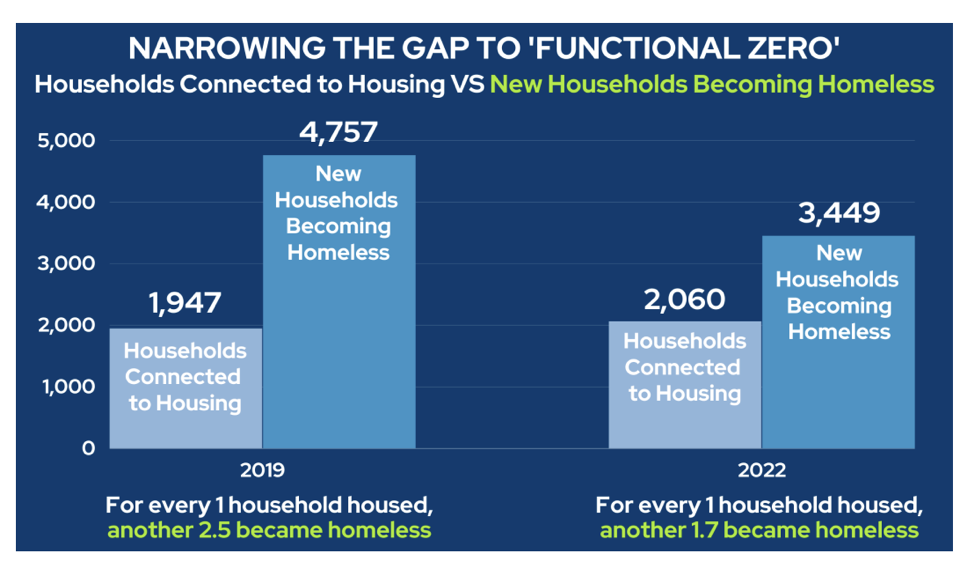

We’ve seen what dedicated federal funding can do. In November 2015, I stood with Jennifer Loving, the CEO of Destination: Home, and County Supervisor Dave Cortese to announce “All the Way Home,” a partnership to end homelessness among veterans. We had many VASH housing choice vouchers specifically issued for veterans, but the rent caps appeared too low for the high rents of Silicon Valley. I joined Housing Authority officials in 2016 to lobby the Obama Administration to lift the caps, and we prevailed. Armed with effective vouchers, the partnership moved 1,940 veterans off the street within five years. By 2021, Loving announced that we had reached “functional zero,” meaning we could house veterans at a faster rate than they were becoming homeless.[20]

That’s what vouchers can do, if we’re deploying them well. They’re worth the investment.

3. Financing Affordable Construction More Nimbly

In addition to more vouchers, we need more housing supply.[21] Throughout our Valley and Peninsula, rental vacancy has remained beneath 4% for most of the last decade and a half due to a vastly inadequate supply. Most of that housing supply must be created by the private sector, without government subsidy.

However, market-rate housing will never be affordable to extremely low-income families, no matter how much of it gets built. The rate at which new housing will “filter down” to become affordable to low-income families requires decades—if it ever happens.[22] To address the current crisis, we need to build more housing that is immediately affordable—that is, rent-restricted.

In 1986, in the wake of the demise of public housing programs, Congress created the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program to support construction of rent-restricted affordable housing by for-profit and non-profit builders. Developers use LIHTC and their syndicators to attract equity investors in their housing projects, reducing the funding that the builder needs to borrow to finance the project. While an imperfect tool that has proven complex and costly to implement, LIHTC is the nation’s largest and most enduring federal tool for constructing affordable housing. Tax credits have provided a stable source of funding for 110,000 new units annually.[23]

The problem is that LIHTCs aren’t terribly “affordable” themselves, because LIHTCs only provide part of the subsidy required to make the construction of any apartment building financially viable. Particularly in the high-cost Bay Area, builders need to find many other subsidies to fill the gap. As a result, we see projects that may have five, seven, or even nine other sources of funding—from state, local, private, or philanthropic sources—in the project’s “capital stack.”[24] Merely arranging these equity and debt deals creates enormous delay and complexity, with conflicting requirements and approval timelines for each funding source. Above all, these complexities add tremendous cost: about $6,500 per funding source in every apartment unit built, according to one study.[25]

Other studies estimate that developing “affordable” housing—with all of the attendant financing and government requirements—costs an additional 19% to 44% more per unit to build than privately-constructed apartments.[26]

Developers and economists alike gripe about the cost, delays, and complexity of the LIHTC program. Regardless, it endures because it’s often the only available federal source of financing for an affordable housing project. In the words of Stephen Stills, “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.”

When construction costs rise rapidly—as they did during the pandemic—developers have to hit the pause button and find more funding to fill the gap, exacerbating another round of delay, thereby increasing costs even more.[27]

Even with successful completion of construction, non-profit housing providers still need to find another source of subsidy—typically a Housing Choice Voucher—to help pay for the management, maintenance, and operations of the facility. If they seek to serve extremely low-income residents, seniors, or formerly homeless people, those services can be very expensive. Currently, LIHTC doesn’t pay for any of that. So taxpayers subsidize the construction of the project, then pay again for a rental voucher for the same tenant.

A streamlined approach would rely on a single funding source for the entire project, and it would save time and enormous public cost. The head of the Santa Clara County Housing Authority, Preston Prince, came up with a great solution: simply boost the value of the tax credits —which are commonly referred to as “4% credits” and “9% credits”—to enable the LIHTC to supplant all of those disparate layers of funding and financing in the capital stack. At, say, a 13% credit, projects could move to construction with only one funding source in the capital stack.

Why not do this? Because it costs more money, of course. A larger tax credit represents more foregone tax revenue. Yet, we could substantially reduce that additional cost, in several ways, and get much more housing, delivered more quickly, at a lower cost per unit.

How? First, the elimination of the many other layers of loans, grants, and other parts of the “capital stack” will reduce much of the expenditure on consultants, syndicators, bankers, and lawyers—that alone would save every affordable project millions of dollars. Based on data from a 2020 Terner Center study, simplifying the capital stack could reduce per-unit development costs by roughly $10 million on a typical 100-unit project in the Bay Area, and the cost savings in accelerating project delivery could be even greater.[28] It would also save state and local governments billions of dollars, which could be better directed to other affordable housing and basic services.

Second, long-overdue reforms in the administration of the LIHTC could save dollars as well. For example, many affordable housing deals are financed on a “cost-plus” basis, which reduces the incentive to lower costs.[29] Some builders inflate estimated budgets to get more credits. Once tax credit allocations are secured, “there are limited incentives to reduce development costs because doing so would mean not using the full appropriated federal [tax credits] issued for the project.”[30] Project costs—and federal money—can be saved by re-engineering the program’s incentives, perhaps by allocating credits against a baseline for private housing construction costs in the region.

Third, the U.S. Department of the Treasury could condition the issuance of some or all of the “super-LIHTC” tax credits on the use of less costly building techniques, such as the prefabricated approach discussed earlier. It could also require that jurisdictions only allocate the credits to project sites that are already zoned for multifamily housing, to save years of public battles, and force cities to do the hard work of rezoning with the community ahead of time. Expediting permitting decisions can dramatically reduce the high cost of delay and indecision but need not bypass community engagement or local control.

Finally, it’s worth exploring whether by setting the credit sufficiently high, a non-profit developer could create a reserve that could be used for operations. If so, it could free up thousands of federal housing vouchers tied to LIHTC projects and instead redistribute them to help many more people get off the street.

Of course, this will still cost something more—but it will do much, much more than it costs. Some context seems appropriate, moreover. During the 1980s, the Reagan Administration cut about 75% of the federal funding for housing construction.[31] Federal support for affordable housing hasn’t recovered, and it shows in the housing burdens endured by millions of American families. The benefits of helping thousands of Americans get off the street and into housing are well worth this modest investment.

4. An Ounce of Prevention Can Save a Pound of Misery

Of all the strategies we’ve deployed to reduce homelessness, by far the most cost-effective initiative had nothing to do with building anything.

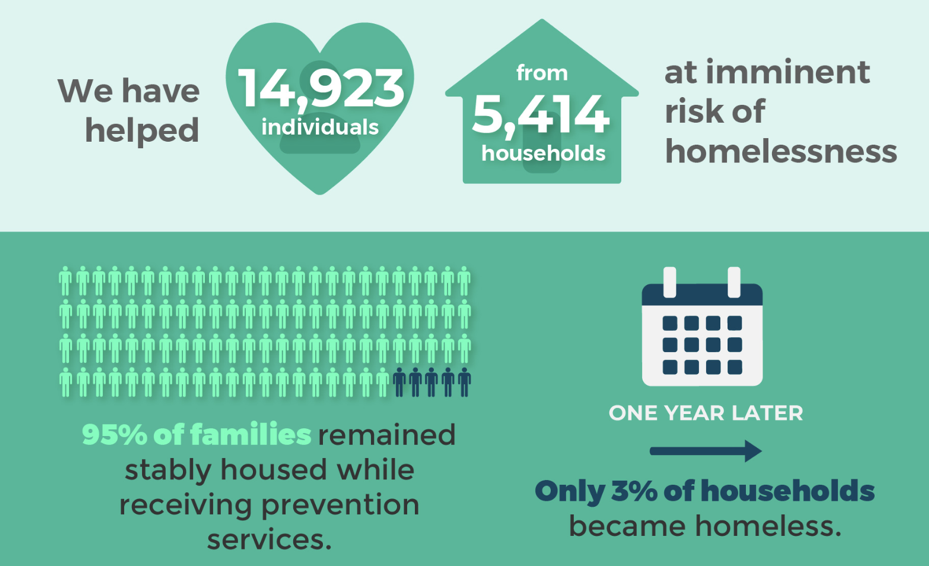

In 2018, Destination: Home CEO Jennifer Loving persuaded me to invest $750,000 of city funding into a pilot program to expand rental assistance and case management to 271 housed San José families. Each of these families had recently experienced a crisis—job loss, divorce, or health emergency, for example—making them unable to pay rent. From the pilot, we learned that simply covering two or three months of rent—at an average of about $3,000—could reduce immense human misery. It also came as a bargain compared to the public cost of people living on the street, which exceeded $83,000 for each of those people needing the highest levels of government intervention such as emergency rooms, police, and emergency medical response, according to a 2015 Santa Clara County study.[32] Best of all, in that first year, 96% of the assisted households remained stably housed—results superior to virtually any other program we’ve tried.

In subsequent years, we doubled down, investing several millions of dollars into a prevention partnership with Sacred Heart Community Services, the county, and Destination: Home, with similar results.

Importantly, we’re starting to turn the corner on reducing the rate at which people are becoming homeless. For years, we worked with partners to house thousands of unhoused people, but found that for every one person we housed, two to three more fell into homelessness. With the help of prevention, we’ve turned the corner, reducing the ratio to 1:1.7 by 2022.

The end goal, of course, is to reduce homelessness to “functional zero.” While we didn’t get there by the end of my term, University of Notre Dame researchers concluded that the program did indeed reduce homelessness, showing promise as a cost-effective intervention for other cities.[33]

San José wasn’t unique. Around the same time, my colleague Oakland Mayor Libby Schaff experimented with a similar program in her city. We shared our experiences with our colleagues, and other California cities proposed programs of their own. UCLA’s Policy Lab leveraged artificial intelligence to help Los Angeles better target dollars to families at the highest risk of homelessness.[34] Rent assistance and casework has since become recognized as a best practice in the battle against homelessness, and as the Policy Lab shows, technology can make them better.

What’s missing in all of this? Federal engagement.

Although we saw hopeful signs with the one-time pandemic-era Emergency Rental Assistance Program, those dollars are now gone. There’s no ongoing federal program for flexible emergency cash assistance for families in crisis. It’s the most cost-effective intervention that we can identify, and it would require fewer bureaucrats to administer than any program in HUD history. Yet, you won’t find a line item for it in HUD’s $73 billion FY2023–24 budget request.[35] In other words, flexible rental assistance as a prevention strategy isn’t on the radar at HUD.

Congress needs to put it there.

5. Eliminating Barriers to Mental Health and Drug Treatment

Finally, confronting homelessness requires better addressing addiction and mental health. Although the percentages vary by subpopulation, roughly 25%-40% of homeless individuals have a substance use disorder (SUD) and 45% have a mental health disorder.[36] While primarily a state and county responsibility, every community relies substantially on federal dollars through Medicaid, Medicare, and federal grants to deliver services.

A political consensus has emerged around the urgency for more mental health and drug treatment of unhoused residents, providing a window of opportunity to focus federal funding in a way that can address the human crises we see daily on our streets. The current system poses many barriers, however, large and small.

The largest obstacle to treatment lies in paltry Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements, which force providers to limit the scope of their services. Momentum for Mental Health recently closed six programs in Santa Clara County for that reason, although the state’s new California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) reimbursement formulas also had much to do with it.[37] Obviously, more money would help—and would be worth the investment.

In other instances, the barriers aren’t about the money. For example, regulations prevent many primary care providers, including those in acute settings like in emergency rooms, from accessing information about a patient’s substance abuse treatment without consent. This inhibits “whole person” care that many experts find imperative. Other barriers limit how treatment can be provided—which explains much about why we don’t see many mental health hospitals anymore.

More Treatment Beds: The Imperative for Inpatient Care

Although best practices call for treating drug addiction and mental illness in the least restrictive setting possible, there appears little question that we face a dearth of inpatient treatment for mental health disorders. In the 1960s, the U.S. had 337 psychiatric treatment beds available per 100,000 residents. Today, that number has plummeted to 12.[38] For people suffering from severe mental illness, the reduction in the number of psychiatric beds correlates strongly with increased rates of homelessness, incarceration, and morbidity.[39]

This appears particularly true for substance use disorder. For unhoused residents addicted to methamphetamine, for example, inpatient care can be critically needed. There is no FDA-approved pharmacological treatment for meth addiction, and meth use increases the risk of severe psychosis and violent behavior, often making outpatient treatment difficult.[40] More treatable substance-use disorders—such as opioid abuse—are still evading treatment because of the difficulties of administering medications like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone on an outpatient basis. One-third of the 1.5 million people enrolled in Medicaid who have opioid use disorder did not receive prescribed medication.[41] While we should prefer less restrictive care settings, too many unhoused and severely ill community members—particularly with dual diagnoses—aren’t getting the inpatient treatment that they need.

Federal restrictions haven’t helped. During a 1960s-era push toward community treatment, Congress prohibited the use of federal Medicaid funding for mental health in facilities with more than 16 beds. Known as the Institution for Mental Disease (IMD) exclusion, it largely cuts off federal funding to large inpatient facilities, making such care much more elusive.[42]

Fortunately, some states have begun to reverse course, reinvesting in inpatient treatment within a continuum of care. California and several other states have applied for what are known as “Section 1115 waivers” to use federal money in larger institutions on an experimental basis for either addiction or mental illness. Only certain counties in California have been approved to pilot the program, however, and the waiver appears revocable and is not permanent.[43]

One challenge with Section 1115 waivers is their uncertain duration. The public and/or private investment in larger facilities requires an ongoing commitment that the treatment will qualify for federal funding. A bipartisan bill, cosponsored by U.S. Representatives Michael Burgess and Ritchie Torres, provides a good first step, allowing Medicaid funding to be used for mental health hospitals.[44]

Some civil rights advocates have pushed back, fearing that it will merely “warehouse” mentally ill people into large institutions. Fortunately, we’ve learned many lessons since that era and need not repeat the mistakes of the past. Moreover, equity demands a parity in resource availability for mental and physical health. Removing the IMD exclusion would ensure that mental health facilities have the same eligibility for Medicaid funding as other healthcare institutions.

Congress can certainly require, as many critics insist, that Medicaid funding be conditioned on ensuring that people with substance use disorders have access to other care they need, including preventive, treatment, and recovery services, all provided in accordance with evidence-based standards.[45] One approach would require what’s known as “bundled reimbursement,” such that Medicaid guidelines would require a residential stay plus outpatient follow-up as a package of care.

Regardless, we need more inpatient care, and we can’t wait years for waivers and other bureaucratic processes. Let’s get Congress to eliminate this statutory relic of the 1960s and get more people the care they critically need.

- “Which US Cities Have the Largest Homeless Populations?” USAFacts, 29 Mar. 2024. ↑

- “HUD Releases 2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report.” National Low Income Housing Coalition, 18 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Campbell, Justin. “San Jose Interim Housing Development Aims to Fight Homelessness.” KRON4, 4 June 2022. ↑

- Greschler, Gabriel. “‘Death Spiral’: It’s Getting Obscenely Expensive to Build Housing in San Jose.” The Mercury News, 26 Oct. 2023. ↑

- “South Bay Will Build 300 Housing Units in Four Months for the Homeless.” KTVU, 23 Oct. 2020. ↑

- Liccardo, Sam. “Make Homelessness Investments Where We See the Solutions.” Medium, 24 June 2021. ↑

- Landers, Jay. “Modular Construction Speeds Delivery of Housing for California’s Homeless.” American Society of Civil Engineers, 9 Feb. 2023. ↑

- Kadah, supra. ↑

- “Homelessness Program Dashboard.” City of San José. ↑

- Pullen, Tyler, et al. “Scaling up Off-Site Construction in Southern California.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Feb. 2022. ↑

- “Policy Basics: The Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 12 Apr. 2021. ↑

- Fischer, Will. “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains among Children.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 7 Oct. 2015. ↑

- Kazis, Noah. “The failed federalism of affordable housing: Why states don’t use housing vouchers.” Michigan Law Review, 2022. ↑

- Kushel, Margot. “Opinion: California’s Struggle with Homelessness Needs Congressional Help.” The Mercury News, 29 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Tegeler, Philip. “Housing Choice Voucher Reform: A Primer for 2021 And Beyond.” Poverty & Race Research Action Council, Aug. 2020. ↑

- Lens, Michael C., et al. “Do Vouchers Help Low-Income Households Live in Safer Neighborhoods? Evidence on the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, vol. 13, no. 3, 2011. ↑

- Fischer, Will, et al. “More Housing Vouchers: Most Important Step to Help More People Afford Stable Homes.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 13 May 2021. ↑

- “Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies (THUD) Appropriations for FY2024.” Congressional Research Service, 26 June 2024. ↑

- “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2023-2027.” Joint Committee on Taxation, 7 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Alaban, Lloyd. “Silicon Valley Veteran Homelessness Reaches New Milestone.” San José Spotlight, 11 Nov. 2021. ↑

- Housing supply turns out to offer a bigger explanation for homelessness than many of us appreciate. Two researchers at the University of Washington sought to determine which factors correlated with high homeless rates, analyzing drug and alcohol addiction, generous welfare benefits, poverty rates, untreated mental illness, and even warm weather. They used advanced statistical techniques to help isolate the key drivers of high homelessness rates among the variables, and found that none of them explained higher or lower homeless rates in any metro. One factor did: the available supply of affordable housing. ↑

- Liu, Liyi, et al. “Geographic and temporal variation in housing filtering rates.” Regional Science and Urban Economics, vol. 93, Mar. 2022. ↑

- “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC): Property Level Data.” Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC): Property Level Data, 12 Apr. 2024. ↑

- Kneebone, Elizabeth, and Carolina K. Reid. “The Complexity of Financing Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Housing in the United States.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Apr. 2021. ↑

- Reid, Carolina. “The Costs of Affordable Housing Production: Insights from California’s 9% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation, Mar. 2020. ↑

- “Federal Housing Assistance: Comparing the Characteristics and Costs of Housing Programs.” U.S. Government Accountability Office, 31 Jan. 2002. The GAO also found that LIHTC units typically cost more than units funded by other supply‐side aid programs. ↑

- “Filling Funding Gaps: How State Agencies Are Moving to Meet a Growing Threat to Affordable Housing.” Abt Associates, 2022. ↑

- Reid, supra. ↑

- “Bending the Cost Curve.” Urban Land Institute, 2014. ↑

- “Affordable Housing Cost Study.” State of Washington Department of Commerce, Sept. 2009. ↑

- Kushel, supra. ↑

- Flaming, Daniel. “Home Not Found: The Cost of Homelessness in Silicon Valley.” Economic Roundtable, 26 May 2015. ↑

- Phillips, David C., and James X. Sullivan. “Do Homelessness Prevention Programs Prevent Homelessness? Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Destination: Home, Apr. 2023. ↑

- Hughes, Abby. “AI Is Helping Outreach Workers in L.A. Predict and Prevent Homelessness.” CBC, 12 Oct. 2023. ↑

- “Budget in Brief.” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2024. ↑

- “Homelessness and Addiction: Ultimate Guide.” Urban Recovery, 7 Jan. 2024. ↑

- Wiener, Jocelyn. “Mental health programs that served hundreds of kids to close after California payment changes.” CalMatters, 21 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Everett, Anita, et al. “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US: Understanding the Problem and Moving toward Solutions.” American Psychiatric Association, May 2022. ↑

- Douglas, Jillian K. “Evaluating the Impact of Federal Mental Health Policy: An Analysis of How Federal Deinstitutionalization Impacted Persons with Severe Mental Illness.” ScholarWorks @ SeattleU, 1 Jan. 2021. ↑

- Lovelace Jr., Berkeley. “Why are there no treatments for cocaine and meth addiction?” NBC News, 7 Nov. 2023. ↑

- Maxwell, Ann. “Many Medicaid Enrollees with Opioid Use Disorder Were Treated with Medication; However, Disparities Present Concerns.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Sept. 2023. ↑

- “Medicaid: IMD Exclusion.” National Alliance on Mental Illness. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024. ↑

- “About Section 1115 Demonstrations.” Medicaid.gov. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024. ↑

- Paun, Carmen. “Mental Hospitals Warehoused the Sick. Congress Wants to Let Them Try Again.” Politico, 1 Jan. 2024. ↑

- Katch, Hannah, and Judith Solomon. “Repealing Medicaid Exclusion for Institutional Care Risks Worsening Services for People with Substance Use Disorders.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 24 Apr. 2018. ↑