Read Sam's book

Crime

When I came into office in 2015, San José had just endured the loss of nearly 600 of its police officers, through pay cuts, pension reform battles, layoffs, and the other consequences of the Great Recession. I rolled up my sleeves to work diligently with the Police Department and then-Police Chief Eddie Garcia to add more than 200 officers to our severely understaffed department between 2017 and 2020 and greatly expanded teams of non-sworn community service officers to respond to less urgent calls.[1] We invested in expanding the work of community partnerships in gang prevention, such as launching a jobs program for at-risk youth, San José Works.

When protests following the murder of George Floyd brought calls for defunding the police (literally to my doorstep, as protestors spray-painted expletives on my home), I refused. I wasn’t going to undo our hard work in rebuilding the department. Instead, I pushed for deep changes in our department, and strengthened the authority of our independent police auditor’s office. When I left office in 2022, San Jose had the lowest homicide rate of America’s 50 largest cities.[2]

As in all big cities, San José’s one million residents still endured too much crime, but the data shows that we didn’t suffer the severe spikes in violence that other big cities faced because of a strong partnership among our police, city gang prevention teams, non-profit organizations, churches, schools, and a host of community partners.[3]

The federal government needs to play a larger role in those partnerships. Here are a few ways it can start:

- Breaking the Connection Between Addiction and Crime

- Preventing Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

- A Sensible Gun Strategy with a Bipartisan Path

- Nothing Stops a Bullet Like a Job and Nothing Unites Us Like Service

- Retail Thefts: A Federal Role

1. Breaking the Connection Between Addiction and Crime

A few months ago, I had the pleasure of speaking with a judge who pioneered the creation of the first drug courts in California in the 1980s, an alternative to the “lock-‘em-up” policies that prevailed at that time. Long lauded as a lion of innovation, he crafted a system that would nudge offenders into treatment. Relying on state laws such as Proposition 36, he would refrain from entering a judgment of conviction where the addicted offender satisfactorily completed the program.

During our call, the judge complained to me that drug courts don’t work anymore. He noted that unless an offender faces the risk of conviction and jail, he simply cannot be incentivized to change his behavior. His words stuck with me: “If nobody can arrest them, and nobody will charge them, then I can’t help them.”

I am not calling for a puritanical approach to drug and alcohol enforcement. We have moved beyond the “War on Drugs” of the 1980s. Criminalizing addiction doesn’t work.

Yet, we also must not put our heads in the sand about the connection between an offender’s drug and alcohol use and their criminal conduct. The efforts of some today to “destigmatize” or rationalize the use of synthetic drugs that are killing 200 Americans each day are deeply mistaken.[4] In the view of many, the pendulum has swung too far.

“Tough Love” Parole for Addicted Non-Violent Offenders

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that most crimes are committed by people who commit other crimes. So, a sensible crime-reduction strategy should start with reducing the recidivism of people already in the criminal justice system: pretrial detainees, probationers, inmates, and parolees.

Most jail inmates either committed their crimes under the influence of drugs or have a substance use disorder.[5] Many studies show that drug use had a role in a majority of crimes of domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, assault, theft, and burglary.[6]

If we can reduce the substance use of addicted offenders, we can have a very direct impact on reducing crime, particularly domestic violence, theft, and assault.[7] There are additional benefits to this crime prevention approach. Reducing drug usage by offenders will sap a key source of revenue for drug dealers and shrink open-air drug markets. It can enable actual rehabilitation of offenders—something that happens too rarely in prisons and jails today—and ensure more families have an earner rather than an onus.

Incarceration might halt the offender’s drug use, but it doesn’t necessarily kick anyone’s habit. Drugs find their way behind bars, but even if they don’t, substance use disorders persist well beyond a term of forced abstinence in prison. For decades, few inmates have had access to substance abuse treatment behind bars. Even for inmates who get treatment, relapse once back out on the street is frequent.[8]

Congress needs to change how the federal prison system puts offenders back into the community. Congress eliminated parole in the federal prison system in 1987, in what one expert called a “big dumb War on Drugs moment.” Without any structured program of supervised release, offenders go from federal detention to the community without a transition. Particularly for those with a drug use disorder, we shouldn’t be surprised when they fail to stay clean or out of trouble.

Congress needs to bring back parole, but with an edge—what I call “tough love parole.” Too often, probation and parole supervision consists of an overwhelmed parole officer with a heavy caseload of inconsistently-supervised individuals who fear neither the rare drug test nor sanction for noncompliance. A better approach to parole would place those offenders with a history of substance use disorder into supervision, with one clear requirement: very frequent drug testing—typically twice per week—with immediate sanctions for failed or missed tests.[9] Sanctions need not constitute a return to a lengthy prison term; a single day or weekend in jail can suffice. The important issue is not the severity of the sanction, but rather that the sanction be swift, certain, and fair.[10]

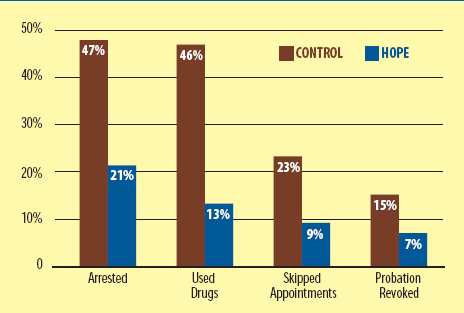

This notion of “swift, certain, and fair” supervision provided the basis for Hawaii Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE), which started in Honolulu and became a national model for reducing crime and substance use. Like many California cities, Honolulu has serious challenges with methamphetamine, a drug with a uniquely intractable grip due to the lack of an FDA-approved treatment. Nonetheless, HOPE demonstrated the power of frequent testing and clear sanctions to modify behavior. One year after their release, HOPE probationers—compared to a control group of probationers convicted of similar offenses—were 55% less likely to be arrested for a new crime, 72% less likely to use drugs, and 53% less likely to have their probation revoked.[11]

As shown by this chart:

Simply, the threat of modest sanctions—typically a day or two in jail—sufficed to substantially reduce dirty tests and recidivism, and these successful outcomes held true when studies were performed on the program ten years later. Other jurisdictions have tried to model programs after HOPE, but they typically fail to deploy the very frequent testing required to make those programs work.[12] Doubling test frequency to twice weekly increases likelihood of detecting drug use from 35% to 80%.[13] Frequent testing becomes critical to change behavior.

How can Congress pay for this? Through reduced incarceration of non-violent offenders in the federal system. Parole typically takes six months off the incarceration term, creating significant cost savings. Those resources can be reinvested into testing, treatment, supervision, and jail for those who fail. Most offenders won’t return to jail, and those who do will have terms that last days, not months or years. Failure and relapse are part of the recovery process, and after a day or a weekend in jail, they can return to their job and family.

Why haven’t we seen more successful approaches like HOPE? Because, politically speaking, it has something for everyone to hate. Some hate the idea of using jail as a sanction for drug relapse—even if it works to help offenders stay clean. Some hate the idea of letting inmates out of prison six months earlier than their sentenced term—even if it saves money.

Criminal justice policy is driven by the extremes: “lock ‘em up” approaches pitted against “catch and release” strategies, such as Santa Clara County’s “depopulate the jail” policy, to which the San Jose Police Department and I strenuously objected in 2022.[14]

I reject both extremes of the pendulum. We must recognize the important and necessary role that jail—with the threat of modest but swift and certain terms—can play in enabling accountability and in changing criminal behavior. “Tough love parole” represents a moment to stop the swinging of the political pendulum—hopefully long enough to allow us to focus on evidence-based reductions in criminogenic drug and alcohol use. By doing so, Congress can save resources, reduce crime, and help offenders rebuild their lives.

Provide Addiction Treatment in Jails and Prisons

Dr. Keith Humphreys, a former Obama Administration official who teaches at Stanford University, believes that Congress can have an even bigger impact on breaking the connection between addiction and crime using a different lever: changing Medicaid rules.[15] Under federal law, a Medicaid recipient’s incarceration deactivates their participation in the plan. While a perfectly-working prison and health care system would instantly restore Medicaid coverage at the moment of release, it doesn’t happen.

As a result, released offenders re-enter our communities with little access to tools to treat the very substance use disorder that landed them in jail. Beyond crime and recidivism in the community, the life of the offender is at stake. In the two weeks after release, former inmates have a death rate 12.7 times higher than other residents, overwhelmingly because of the high rate of drug overdose.[16] Inmates usually lose physical tolerance for opioids and other drugs during their forced abstinence in custody, making their return to use extremely dangerous.

Last year, a bipartisan group of members of the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a bill, the Medicaid Reentry Act, to provide Medicaid coverage to people in the last 30 days of their prison or jail sentence.[17] A similar change in Rhode Island reduced post-incarceration overdose deaths by two-thirds after the program was introduced.[18] At the very least, enabling Medicaid coverage for treatment of mental health disorders and addiction would more than pay for itself in averted harm, both to the community and the offender. Although a state-by-state waiver process exists for states willing to fund correctional health care in this way, the process is a “slow-moving train at a time when we need high-speed solutions to the opioid epidemic,” according to Dr. Humphreys. Congress must pass the Medicaid Reentry Act—or something like it—immediately.

2. Preventing Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence

Twenty years ago, as a young Deputy District Attorney in Santa Clara County, I received an ominous promotion from my boss, District Attorney George Kennedy: I was being sent upstairs to the “Sex Crimes” Unit. That unit handled some of the most difficult criminal litigation in the office—but those cases were also some of the most important and impactful.

A year later, I found myself pacing up and down a hallway in a Palo Alto courthouse, where a 15-year-old survivor, who I’ll call “Mia,” sat trembling near the women’s bathroom. She had to testify. Even worse, she had to do so the day after her best friend had told the jury that Mia was lying about her victimization. I knew better, of course. The 20-year-old defendant’s gang affiliation ensured that his buddies would threaten several witnesses like Mia’s friend. The trial was going south, though, and I feared that an acquittal would put the defendant back in the very neighborhood where Mia and her family lived.

I saw Mia spend most of that morning inside the bathroom, throwing up into the toilet, while her rape crisis counselor, Lara, held her hair. Mia asked, for the fourth or fifth time, if she could avoid testifying.

My heart sank. I told Mia that it was her choice, and she could always choose not to testify. I wasn’t going to compel her to do so against her will. Then I had to tell her the truth: “If you don’t testify, I don’t have any way of keeping you safe. The defendant will walk out of court with an acquittal, and he’ll be back in your neighborhood.” It was the brutal reality of our criminal justice system, but her counselor agreed that Mia needed to hear the truth.

Mia courageously walked into the courtroom later that afternoon and sat in the witness box, only a few feet away from her young assailant—just as the Sixth Amendment requires of all witnesses. She trembled and stuttered, but collected herself to recount every detail of her horrible encounter with the defendant. Overwhelmed with stress and anxiety, she nearly fainted on her way out of the courtroom as her mom and counselor held her up.

I’ve never seen a more courageous young person. Fortunately, the defendant took the stand, and I had an opportunity to cross-examine him on every bit of his false testimony. The jury convicted him after four days of deliberation.

Mia’s mother gave me a hug as we celebrated the end of the trial, but minutes later, she reminded me that Mia’s trial would continue as she took the next steps in her healing and resuming her young life. Months later, the judge sentenced the defendant to 19 years in prison.

I occasionally think about that day and consider what Mia’s life would have been like if she hadn’t mustered the strength to testify. In particular, I think about how her courage might well have prevented another woman from experiencing the horror she endured, at least for the 19 years of her assailant’s prison sentence. She felt empowered to make that choice, though, because she had the support of a rape crisis counselor, and because she was given the hard truth about the need to testify.

We need to do more to empower survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence. Doing so will put them in a better position to protect themselves and others. We can start by ensuring that they have all of the support that they need. And we can ensure that we tell them the truth. Both will help survivors make the best decision they can about whether to report their victimization to the police for a crime that is already so severely underreported.

Rape Crisis Centers and Victims of Crime Act Funding

Every year, organizations serving survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault await word of the congressional appropriation for their programs under the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA). VOCA funding provides “the backbone to California’s response to crime victim’s needs,” and organizations are bracing for reductions of more than $100 million in federal funding to the state in mid-2024.[19] The folks depending on that funding include groups providing emergency shelter and transitional housing to tens of thousands of domestic violence victims and their families, seeking to flee their abusers. They include rape crisis centers that served more than 46,000 survivors last year, helping to inform them about counseling and services, and enabling them to navigate often perplexing criminal justice and social service systems. They helped 15,000 elder abuse victims, and more than 1,100 human trafficking survivors last year.[20]

Obviously, this work is critical for thousands of Californian survivors, who have suffered enough already. In many ways, it can also prevent future victimization. A battered spouse and children who have found stable housing will be far safer than if they continued to live under the same roof as their batterer. Child sexual assault victims who are supported in their decision to report to the police and testify against their abuser will thereby reduce the risk of harm to other children. Congressional appropriations—what Congress is actually spending—clearly falls short of its budgetary authorization for this life-saving program.

None of my other proposed solutions for congressional action consist of a simple admonition to “fund the program.” But this one is: Congress, fund the Victims of Crime Act.

Telling Survivors the Truth

Rideshare and taxi companies operate platforms that necessarily pose risks for drivers and passengers alike, through no fault of those companies. That is, driving anyone to a destination will leave them (or you) isolated and without help. Tragically, thousands of sexual assaults are associated with these taxi and rideshare platforms every year. In 2019, one company reported that it had received 3,045 reports of sexual assault over the prior two years.[21]

To their credit, rideshare companies in recent years have substantially improved their protocols to elicit reports from survivors, remove accused assailants from platforms, and support survivors with information. They have created elaborate systems to ensure that trained personnel would receive allegations of sexual assault and report them up the company chain.

There are just two things that the taxi and rideshare companies generally don’t do. First, they generally don’t call the police to report the crime. Second, they generally don’t tell the survivor that the company won’t be calling the police.

If the police aren’t called, then there’s no report to the DA, no charges filed, no restraining order sought, and no consequences for the assailant. In other words, nothing happens. The companies will describe in detail how they take great pains to remove the alleged offender from their rideshare platform. The problem is that they’re still out on the street, posing a risk to unknowing future victims.[22]

As I learned more about this from media accounts, I became puzzled about how this could persist, with thousands of assaults happening on these platforms and in taxis every year.[23] I called Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen and Supervising District Attorney Terry Harman. We agreed that something had to be done.

Through calls and Zoom meetings over several months, we sought to engage the companies’ executives and government affairs staff in conversation, seeking to persuade them to report sexual assaults on their platforms to the local police. We had no leverage and no legal way to require them to do so. I threatened a city ordinance, but industry-friendly state regulations would likely trump anything that the city might legislate.

When Terry, Jeff, and I sought transcripts of the companies’ protocols for responding to survivors’ reports of abuse, it became apparent that the companies did not make it a practice to affirmatively inform survivors that disclosing the assault to the rideshare company would not result in any referral to the criminal justice system. No criminal investigation would result. No arrest. No prosecution. No restraining order. No sentence or prison term. No restitution. Nothing. We have no way of knowing how many survivors believed otherwise, particularly in this age of “mandated reporters,” in which we expect that many people in positions of authority must report sexual abuse to the police.

In other words, the companies had no obligation to affirmatively tell the survivors the truth. Just as I had to tell 15-year-old Mia the truth to enable her to make an informed decision about whether to testify in front of her rapist, the companies need to tell the truth to reporting victims to ensure they can make a well-informed decision about whether they should go to the police.

For victims, the situation was (at least implicitly) misleading. We suspected—based on accounts from several survivors—that survivors believed their reports would be conveyed to the police, and “something would be done.” The rideshare companies did tell them about “investigations” that would follow. But the companies never proactively transformed their “company investigations” into “criminal investigations.” Nobody mentioned to victims that the investigations would remain confined to the four walls of headquarters, and police would likely never see their reports. The police could always ask for the specific case, but only if they actually knew to ask for it—and local police departments would never know to ask if nobody disclosed the rape or sexual assault to begin with.

We held hearings and talked to the media. The New York Times covered our efforts.[24] But as the months of negotiation continued, the companies ran out the clock. Our final public hearing occurred in December of 2022, a few days before I was scheduled to “term out” after my full two terms as mayor.

Congress needs to step in. At the very least, taxis, rideshare companies, and any other corporate entity that receives a report of sexual assault victimization must clearly tell the reporting party that their report to the company will not result in any action by the criminal justice system. They should be told that they can get a restraining order, an arrest, or restitution only if they themselves call the police. And they should provide the survivor with the phone number for the local police department’s sexual assault unit, if they have one, so that specially trained detectives can take the report.

Sexual assault survivors have enough burdens to grapple with already. Congress needs to ensure that they get the whole truth, to enable them to make the best decisions for themselves and their communities.

3. A Sensible Gun Strategy with a Bipartisan Path

The single worst day of every big-city mayor’s career is exactly the same. It starts with a call from police brass, and the only memorable words are “active shooter.” Recollection blurs in a swirl of emotions, mixing adrenaline, horror, and worry.

I’ve had two of those days in my career. In the first, a young man killed three victims at the Gilroy Garlic Festival, and two of those victims were children living in my city.[25] As I attended an outdoor memorial for six-year-old Stephen Romero, I vividly remembered one outraged cousin of Stephen’s who confronted me in Spanish, “¿Qué haces tú, Alcalde?” That is, “What are you going to do about this, Mayor?”

She was right. But I also knew our options were very limited. Federal and state law wouldn’t allow my city or any other to tax guns, prohibit assault weapons, create a registry, or license guns. The courts, Congress, and the states have all hamstrung cities from responding to gun violence through a thicket of preemptive laws and prohibitions on local regulations. In a nation of 400 million guns, there aren’t any easy options left. But we had to do something.

I had already been working for several months with gun violence experts and lawyers to find a constitutional response. It was time for us to air the proposed solution: the nation’s first-ever requirement for gun owners to pay fees to support violence reduction efforts, and to carry insurance to compensate victims. Many studies show that in every episode of intimate partner violence or depression, outcomes are much more likely to be fatal if there’s a gun in the home.[26] If we could generate the resources to provide mental health treatment, domestic violence services, suicide prevention, and safe storage information to people living in homes with guns, we should be able to reduce deaths and injuries.[27]

After several publicized hearings and battles, the city council approved the measure in early 2022. As expected, several gun groups immediately filed lawsuits, but top trial attorneys Joe Cotchett and Tamarah Prevost volunteered to represent the city pro bono. A federal district court upheld the constitutionality of our measure in 2023, and the measure now awaits the approval of the Ninth Circuit before it will launch.

As the New York Times captioned my op-ed on the subject, “400 Million Guns Aren’t Going to Just Go Away. In San José, It’s Time to Try Something New.”[28] It’s time to try something new in Congress as well.

This divided Congress is unlikely to approve as bold of a proposal as my city council. Yet, there’s plenty that even a polarized Congress should be able to agree upon and approve with the right leadership. I’ve laid my ideas into three basic strategies: keeping guns out of the wrong hands, giving the police the information they need, and regulating ammunition.

Keeping Guns From Dangerous Hands: “Red Flags,” Loopholes, and Enforcement

In October of last year, the sister of an Army reservist in Maine called the Army to notify them that her brother was hearing voices and experiencing acute mental distress. Maine had a very weak “yellow flag” law, however, which required multiple, time-consuming bureaucratic steps before authorities could remove guns from her brother’s home.[29] Weeks later, he killed 18 people and injured 13 more in a bowling alley and restaurant in Lewiston.

Twenty one states have stronger “red flag” laws—also known as extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws—than Maine’s, with fewer procedural steps. Other states have watered-down versions, or no such law at all. However, about one-third of mass shooters clearly evince dangerous warning signs to others before a killing,[30] and 80% of suicidal individuals do the same.[31] Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of red flag laws in preventing violent attacks.[32] A uniform national red flag or ERPO law is long overdue, and Congress must pass it.

Such laws are just one tool among several—such as background checks, prohibitor laws, and surrender laws—that we can use to keep guns away from those who pose unreasonably high risk of harm to others because of prior convictions, existing restraining orders, or court determinations of incapacity.

Background checks amount to politically low-hanging fruit, since we should all agree with keeping guns away from violent people. The good news: we generally do agree, as provisions to close loopholes on background check requirements and enforcement poll well among both Democrat and Republican voters. More importantly, background checks actually work in reducing both homicides and suicides in many studies.[33]

Where states have not done so, Congress must broaden prohibitor laws to match the best practices to keep guns away from people inclined to violent behavior. Congress could ensure that all violent convictions result in a prohibition of gun possession. Currently, most states prohibit gun possession for anyone convicted of a felony or a domestic violence misdemeanor. Yet, other violent misdemeanors, such as assault and battery, do not carry that sanction. If we’re concerned about violent offenders carrying guns, then any misdemeanor should suffice—particularly since many of those convictions were actually charged as more serious offenses, and negotiated away during plea bargaining.

Congress must also close dangerous loopholes. Federal law currently allows 45% of recent gun purchasers to avoid background checks by purchasing firearms from an unlicensed gun dealer.[34] Another dangerous gap in the law—known as the “Charleston Loophole” for its role in that horrible attack—enables gun sales to proceed after three days, even if the background check awaits completion. As a result, 5,800 illegal purchasers obtained a gun using this loophole in 2020 alone.[35]

Most importantly, we need to better enforce existing laws. Many states don’t mandate the surrender of guns after a conviction or court order. Relinquishment of firearms by prohibited persons is crucial; for example, one study found that a state law’s mandate to domestic abusers to relinquish weapons reduced intimate partner homicide by 10%.[36] Congress must preempt weak state laws with a federal mandate.

Ultimately, enforcement requires supporting understaffed local police departments to fund specialized units of officers who take on the very dangerous work of showing up at the homes of probationers, parolees, or restraining order subjects to check for and seize weapons. While this idea comes with a price tag, it also comes as a bargain relative to the price of violent felons keeping their guns.

How can we pay for it? An ammunition tax—similar to the federal excise tax that Congress has imposed on gun sales since 1919—would be a logical vehicle, depending on how courts resolve its constitutionality. The Illinois Supreme Court struck down a Cook County ammunition tax in 2021, but the California legislature enacted a new ammunition tax anyway last year.[37] Obviously, getting an ammunition tax passed would need to await a Democrat-led Congress, at the very least. The outcome of the contentious litigation due on the California law will likely provide helpful guidance for Congress’ next steps.

Enabling Law Enforcement to Use Purchasing Records

Through a series of provisions, particularly one known as the “Tiahrt Amendments,” Congress hamstrings law enforcement from accessing gun data critically needed for investigation, enforcement, and prosecution. For example, the law requires the FBI to destroy all approved gun purchaser records within 24 hours of approval, making it extremely difficult to retrieve firearms from prohibited persons who possess guns.[38] It also makes efforts to trace gun use more difficult in criminal investigations. Congress needs to allow the FBI to retain these firearm sales records in a central database, as some states do, and use them to quickly trace the ownership of guns recovered in crime.[39] This data also protects cops responding to emergency calls by letting them know whether people in a residence own a firearm, and enables cops to enforce possession prohibitions on people ineligible to own them.

The same provisions prohibit federal agencies from requiring gun stores to report inventories, an essential tool for identifying and combating the flow of stolen guns to criminal organizations, which exceeds tens of thousands of firearms annually.

Nobody’s Second Amendment rights are infringed by giving the police the information they need to stay safe and enforce the law. Congress needs a much more sensible approach to data that supports law enforcement.

Regulate Ammunition Like It’s Dangerous—Because It Is

Finally, there’s ammunition. In a nation with 400 million guns, scarcer bullets could help. Ammunition remains exempt from many of the regulations that apply to gun ownership, such as dealer licensing, background checks, ammunition sales record-keeping, and regulation of high-volume sales.[40] It’s not for lack of popular support: a New York Times survey found that 73% of respondents supported laws requiring background checks on purchasers of ammunition, and 64% support limits on purchases of ammunition.[41]

Sensible limits on ammunition purchasing seems obvious enough. At the 2012 mass shooting in the Aurora, Colorado movie theater, for example, the shooter ordered 6,000 rounds of ammunition and a 100-round magazine from an unlicensed online retailer. It’s time for Congress to step up.

Of course, there is plenty more for Congress to do to reduce gun violence. For instance, as Mayor of San José, we enacted a safe storage mandate and a first-in-the-nation liability insurance coverage mandate for all gun owners that I hope will engage insurance companies in incentivizing safer storage practices, among other behavioral changes. In Congress, I would join efforts to pass Ethan’s Law, a common sense piece of legislation named after a Connecticut teen who was tragically killed in 2018 by an unsecured gun in a neighbor’s home.

And we can reinstate the assault weapons ban. The late Senator Dianne Feinstein championed this law, having seen up close the deadly impacts of gun violence. Unfortunately, it was allowed to expire in 2004—and in the decades since, we have lost countless lives in tragedies involving assault weapons. It’s long past time for Congress to renew this law.

4. Nothing Stops a Bullet like a Job, and Nothing Unites Us Like Service

“Nothing Stops a Bullet Like a Job” is the moniker of Homeboy Industries, a non-profit enterprise created by Jesuit priest Fr. Greg Boyle, to engage current and former gang members in a host of businesses that would help to revitalize their corner of South Central Los Angeles.[42]

The insight of Homeboy Industries is captured well in academic literature. A summer job program in Chicago, focused on youth in gang-impacted neighborhoods, reduced violence by 43% in 16 months.[43]

Our young adults might be the most idealistic, energetic generation in history. My teaching in classrooms at Stanford University and San José State University reminded me of that daily. The communities that will prosper in the next decade will harness that energy.

In my first year in office in San José, we launched a jobs program for youth, San José Works, with a particular focus on at-risk teens living in East San José. We helped more than 5,000 young people land their first jobs, along with financial literacy classes, support and guidance for “soft skills” development, and college preparedness. What struck me about my conversations with so many of the students was their tremendous interest in working for the city. They genuinely enjoyed working with seniors at our community centers, tutoring students at our libraries, and caring for our parks. They embraced the value of public service. They wanted to do work with a greater purpose.

That lesson about the power of service stuck with me when the pandemic began. As we assembled a strategy to support our recovery, I worried deeply about the thousands of young people in our most vulnerable communities who could not work to support themselves or their struggling families.

Fortunately, we had some flexible federal funding for pandemic relief. I refused to use that funding solely to backstop “business as usual” city operations (and our city fortunately was in pretty decent fiscal condition), so we focused on how we could most effectively deploy the funding to respond to our community’s most urgent needs. We needed help with food distribution to keep struggling families fed. We needed to support vaccinations and testing that the county was doing at city sites. We had thousands of kids falling behind because of shuttered schools.

I huddled with our team and community partners like Dorsey Moore at the San José Conservation Corps. I proposed a new variant of our jobs program: the San José Resilience Corps.[44] We would pay hundreds of young adults—primarily living in our lowest-income census tracts—to serve the community. They worked in food warehouses with Second Harvest Food Bank, supported vaccination and testing outreach with Gardner Healthcare, tutored kids in our libraries, and worked through the Conservation Corps to help prepare for the next wildfire season by clearing brush in outlying neighborhoods. Through these and other efforts, our city team started to identify career pathways for young people in our Parks and Libraries departments, and a career recruiting and training element became prominent. The city department heads began to see the Resilience Corps as a recruiting tool to deal with persistent vacancies in key departments at City Hall.

This idea is not a new one. More recently, President Joe Biden has embraced it in a proposal to create an American Climate Corps (ACC) at the federal level, to engage young people from struggling neighborhoods in climate-related work including solar panel installation, natural disaster resilience, and ecosystem restoration.[45]

It’s an idea whose time has come in this deeply divisive moment in our nation. Amid all that divides us, there is something that unites us: service. We all honor the service and sacrifice of those who have fought for our country to defend our freedom. We express gratitude to our teachers for their service, and, especially during the pandemic, to our health care personnel. All of us do so—Republican or Democrat. The call of service to our country and our community is a common calling to each of us to rise above our petty differences.

The challenge is that Congress hasn’t funded the ACC. For now, it remains a seed of an idea, funded within the department budgets in an interagency collaboration between AmeriCorps, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Departments of Labor, Interior, Agriculture, and Energy. Although President Biden aspires to train and employ 20,000 workers through the ACC, for now it amounts to a small pilot program in New York employing 80 people in forestry.[46]

We can do far more. With little or no congressional funding, we could engage with private sector companies starved for labor. HVAC contractors could help train and employ thousands of young adults to replace gas, air conditioning, and water-heating systems with electric heat pumps in millions of homes. We could help thousands of homeowners install insulation, or gray water systems, or battery systems, in partnership with the trades and local businesses. We simply need to engage a national network of mayors who routinely make these private-public partnerships happen every day in their communities. We could enable many more Americans to participate in the green revolution, and provide real, non-exportable job skills to thousands of young people.

We could do even more if Congress funded it. I’d adapt a similar idea from my friend, Peter Dixon: shift the program under the Army Corps of Engineers (ACE), to provide training pathways for ACE employment, thereby funding the program within the Defense Department budget. Several of the items on the Pentagon’s lengthy list of antiquated procurement programs (see my section on “Innovation Economy” online) would provide more than ample investment.

We’ve made it through most of the description of this initiative without mentioning crime. Crime reduction, of course, is just one of the many benefits of employing young adults—ensuring that they won’t be distracted by less constructive activity. Like public service, it’s not a new idea. It’s simply an idea whose time has come.

5. Retail Thefts: A Federal Role

Retail theft rings have become emboldened throughout many U.S. cities, terrorizing small business owners, intimidating customers, and driving up costs for consumers.[47] Some high-profile commercial burglaries and larcenies in the Bay Area have turned violent.[48] Meanwhile, every shopper pays a “theft tax” that reflects the store owner’s higher cost of doing business, assuming they still are willing to do business.[49] Retail store closures in high-theft environments like San Francisco leave too many cities pockmarked with vacant storefronts.

Much controversy in California still swirls around the 2014 approval of Proposition 47[50] and what the California legislature has sought to do about it, and the proposed Proposition 36 on the November ballot. Regardless of how California voters resolve those issues in November, Congress can do its part to help address the problem of retail thefts and burglaries that have plagued all of our communities. It’s important to explore the root of the controversy, however, to understand how Congress can help.

Prop 47 relegated thefts and burglaries of property worth less than $950 to “misdemeanor” status, rather than felony. In California, as in most states, police officers cannot arrest anyone for committing a misdemeanor, unless it is committed in the officer’s presence. Instead, the officer issues a citation, with a notice to appear in court. Since many thefts, auto break-ins, and burglaries involve property worth less than $950, police can no longer arrest petty thieves caught red-handed on store cameras.

Beyond the statistics and studies, emotional motivation plays a role in this story, to be sure. Undoubtedly, thieves have felt emboldened by the lack of immediate consequence—an arrest—for their crime. Cops complain that the law has been demotivating to those colleagues who want to “arrest bad guys” and are too busy racing to high-priority calls to be issuing tickets. Many frustrated store owners and restaurateurs simply stopped calling the cops—meaning that none of those crimes even get into the crime data to assess Prop 47’s impact.

At his Foxworthy and Naglee grocery store locations in San José, Fred Zanotto told me he stopped reporting the two or three daily petty thefts he endures because he’s tired of calling cops who can only shrug their shoulders. The Walmart on Monterey Road keeps virtually every toiletry behind locked windows because so many would “disappear” each day. An attendant told me that many shoppers simply bypassed that section of the store because they feel it’s too much trouble to keep asking somebody to unlock the display case to get some deodorant. Again, these stories aren’t captured in the data, but they all impose costs on restaurants and retailers.

Here’s the gist of it: arrests matter. Many studies support the notion that criminal deterrence depends far more on the certainty of getting caught than on the severity of punishment.[51] We don’t need long jail terms to deter thieves. We don’t even need felony charges to be filed. We do need arrests. Regardless of what Prop 47 did or didn’t do, we need to arrest crooks to deter crime.

Congress can help. A new federal theft ring statute could enable felony prosecution of higher-level fencing of stolen goods to address the criminal groups that fuel a substantial amount of theft activity. Currently, federal law unnecessarily places an interstate travel requirement on federal enforcement of theft, with a high monetary threshold for charging.[52] For the routine thefts that support a commercial criminal enterprise like a theft ring, Congress could set a lower threshold—say, $500—for felony arrest, though not for filing federal charges.

Within the legislation, Congress would “cross-designate” local police officers and local prosecutors for new federal theft ring task forces. Typically, local city police officers can’t arrest suspects for federal offenses, and local DAs don’t prosecute them. But in unique cases—such as under federal drug laws—federal statutes can authorize local police and prosecutors to be “cross-designated” as “federal agents” for purposes of federal investigation and enforcement.[53] As a federal prosecutor, I occasionally worked with local police officers in the 1990s on international narco-trafficking cases, and the partnership proved essential for our ability to connect the evidentiary dots between cocaine smugglers, warehouse owners, and money launderers.

In this way, Congress can empower local cops in every state to deter petty thefts with actual arrests—even if those thieves don’t face federal charges or prison terms—regardless of the varying state laws that prevail in each jurisdiction. More importantly, we can ensure local and federal authorities gather arrest data that identifies participants in larger theft rings and criminal gangs. Those participants may become future witnesses in a prosecution of the ringleaders.

We must be clear about what such a law should and shouldn’t do. The law must not result in the charging of petty thieves with federal felony offenses. The goal here is arrests, not long sentences nor even felony charges.

The law can do so in various ways. A federal statute could mandate a diversion program to enable first-time or low-level offenders to voluntarily enter a program to avoid a conviction or jail term.[54] That is, a typical “deferred entry of judgment” program would allow any first-time or minor offender to avoid a conviction on their criminal history by completing a program that might include, for example, substance abuse treatment or weekend work.[55] Alternatively, the statute might require high prosecutorial thresholds, which govern the charging decisions of DAs and U.S. Attorneys. In this case, the law could ensure that on standalone offenses, no charges could be filed unless the crime meets a minimum of, say, three separate incidents meeting a high valuation of loss, the use of a gun, or some other aggravating circumstance. In other words, first-time and petty thieves generally won’t see charges filed, and they won’t likely experience more than a few hours in jail, given constitutional constraints on holding an arrestee without charges.

So, why do it? Again, the threat of arrest does much more to deter crime than the severity of punishment.[56] Repeat arrests, moreover, may bring actual felony charges and a significant jail term. And in every case, an arrest will develop data—fingerprints, photos, witness statements, and the like—that cops and prosecutors can use to link multiple cases together. They may link rings of thieves, or they may connect petty offenses to more serious robberies and violent crimes. The ability to simply get arrestees into an investigatory database is of tremendous value for detectives.

Federal-local cooperation has proved essential in helping local communities struggling with organized crime rings for decades. It’s time to put it to work to help small business owners and their neighbors put a stop to widespread theft and burglaries.

- Liccardo, Sam. “The Back Story: The Facts About Police Staffing.” Medium, 15 Aug. 2022. ↑

- Fox, supra. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Humphreys, Keith, and Jonathan Caulkins. “Destigmatizing Drug Use Has Been a Profound Mistake.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 12 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Belenko, Steven, et al. “Treating substance use disorders in the criminal justice system.” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 15, no. 11, 17AD. ↑

- Marlowe, Douglas B. “Integrating Substance Abuse Treatment and Criminal Justice Supervision.” Science & Practice Perspectives, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2003. ↑

- Harrell, Adele, and John Roman. “Reducing drug use and crime among offenders: The impact of graduated sanctions.” Journal of Drug Issues, vol. 31, no. 1, Jan. 2001. ↑

- Greenfield, Shelly F., et al. “Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 86, no. 1, Jan. 2007. ↑

- Kleinman, Mark A. R. “Controlling Drug Use and Crime Among Drug-Involved Offenders: Testing, Sanctions, and Treatment.” Drug Addiction and Drug Policy: The Struggle to Control Dependence, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2001. ↑

- Grasmick, Harold G., and George J. Bryjak. “The deterrent effect of perceived severity of punishment.” Social Forces, vol. 59, no. 2, Dec. 1980. ↑

- “‘Swift and Certain’ Sanctions in Probation Are Highly Effective: Evaluation of the Hope Program.” National Institute of Justice, 2 Feb. 2012. ↑

- Nolan, Pat. “‘Swift & Certain Probation Sanctions’ Expand to 18 States.” Prison Fellowship, 8 May 2013. ↑

- Kleinman, Mark A. R. “Opportunities and Barriers in Probation Reform: A Case Study of Drug Testing and Sanctions.” U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, June 2002. ↑

- See Larson, Amy. “‘Catch and Release’ Doesn’t Work for Criminals, San Jose Mayor Says.” KRON4, KRON4, 27 July 2022. Specifically, the SJPD and I released data showing that in a prior 16-month period, frustrated SJPD cops had to arrest, and re-arrest, the same 103 suspects ten or more times, and the same 887 arrestees more than 5 times. ↑

- Humphreys, Keith. “Expanding Medicaid Coverage to the Incarcerated and Those Recently Released.” Washington Monthly, 17 Apr. 2023. ↑

- Binswanger, Ingrid A., et al. “Release from prison — a high risk of death for former inmates.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 356, no. 2, 11 Jan. 2007. ↑

- “H.R.2400 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Reentry Act of 2023.” Congress.Gov, 30 Mar. 2023. ↑

- Vestal, Christine. “This State Has Figured out How to Treat Drug-Addicted Inmates.” Stateline, 26 Feb. 2020. ↑

- “Statement from the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence and Valor on Anticipated Cuts to Critical Funding.” California Partnership to End Domestic Violence, 22 Aug. 2023. ↑

- “VOCA Funding Advocacy.” California Partnership to End Domestic Violence. Accessed 30 Aug. 2024. ↑

- “US Safety Report.” Uber, 5 Dec. 2019. ↑

- Przybylski, Roger. “Adult Sex Offender Recidivism.” U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, Mar. 2017. ↑

- O’Brien, Sara Ashley. “Uber Releases Safety Data: 998 Sexual Assault Incidents Including 141 Rape Reports in 2020.” CNN, 30 June 2022. ↑

- Metz, Cade. “Silicon Valley County Battles with Uber over Reporting of Sexual Assault.” The New York Times, 3 Oct. 2022. ↑

- Johnson, Alex, et al. “Three Dead, Suspect Killed in Shooting at Gilroy Garlic Festival in California.” NBC News, 29 July 2019. ↑

- Dahlberg, Linda L., et al. “Guns in the home and risk of a violent death in the home: Findings from a national study.” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 160, no. 10, 15 Nov. 2004. ↑

- Barber, Catherine, et al. “Linking public safety and public health data for Firearm Suicide Prevention in Utah.” Health Affairs, vol. 38, no. 10, Oct. 2019. ↑

- Liccardo, Sam. “400 Million Guns Aren’t Going to Just Go Away. in San Jose, We’re Trying Something New.” The New York Times, 21 Dec. 2022. ↑

- Chan, Melissa. “Maine’s ‘Yellow Flag’ Law Scrutinized as ‘Woefully Weak’ after Mass Shooting.” NBC News, 27 Oct. 2023. ↑

- “Extreme Risk Laws Save Lives.” Everytown Research & Policy, 1 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Fingar, Kathryn R., et al. “Two Decades of Suicide Prevention Laws: Lessons from National Leaders in Gun Safety Policy.” Everytown Research & Policy, 29 Sep. 2023. ↑

- “Extreme Risk Laws Save Lives,” supra. ↑

- Rich, John A., et al. “How combinations of state firearm laws link to low firearm suicide and homicide rates: A configurational analysis.” Preventive Medicine, vol. 165, Dec. 2022. ↑

- “Universal Background Checks.” Giffords Law Center, 2024. ↑

- “Which States Have Closed or Limited the Charleston Loophole?” Everytown Research & Policy, 4 Jan. 2024. ↑

- Díez, Carolina, et al. “State intimate partner violence–related firearm laws and intimate partner homicide rates in the United States, 1991 to 2015.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 167, no. 8, 19 Sept. 2017. ↑

- Gorman, Steve. “California Enacts First State Tax on Guns, Ammunition in US.” Reuters, 27 Sept. 2023. ↑

- “Tiahrt Amendments.” Giffords Law Center. ↑

- “Maintaining Records of Gun Sales,” Giffords Law Center. ↑

- “Ammunition Regulation,” Giffords Law Center. ↑

- Sanger-Katz, Margot, and Quoctrung Bui. “How to Reduce Mass Shooting Deaths? Experts Rank Gun Laws.” The New York Times, 5 Oct. 2017. ↑

- Dickerson, Justin. “‘Nothing Stops a Bullet Like a Job’: Homeboy Industries and Restorative Justice.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 3 May 2011. ↑

- Heller, Sara B. “Summer Jobs Reduce Violence Among Disadvantaged Youth.” Science, vol. 346, no. 6214, 5 Dec. 2014. ↑

- Teale, Chris. “Cities Turn to Resilience Corps as Pandemic Recovery Tactic.” Smart Cities Dive, 22 Mar. 2021. ↑

- “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Launches American Climate Corps to Train Young People in Clean Energy, Conservation, and Climate Resilience Skills, Create Good-Paying Jobs and Tackle the Climate Crisis.” The White House, 20 Sept. 2023. ↑

- “Applications to Join New American Climate Corps Program, AmeriCorps NCCC Forest Corps, Now Open.” AmeriCorps, 1 Dec. 2023. ↑

- Miller, Harrison. “Retail Theft Losses Mount From Shoplifting, Flash Mobs — And Organized Crime.” Investor’s Business Daily, 6 Oct. 2023. ↑

- “Attorney General Bonta Announces Charges against Three Suspects in a Bay Area Organized Retail Crime Ring.” State of California Office of the Attorney General, 17 Jan. 2024. ↑

- Kou, Lydia. “Opinion: ‘Theft tax’ is costing California families more than $500 per year.” Mercury News, 5 Oct. 2023. ↑

- “Felony Theft Amount by State 2024.” World Population Review, Jan. 2024. Studies suggest that Prop 47’s actual impact on crime rates may be more hyperbole than fact; thefts did increase 9% in California after its passage, while arrests dropped measurably, but other crimes have not increased. Nonetheless, most states actually have even higher felony thresholds for theft than California’s, so this problem is certainly not unique to California. ↑

- Nagin, Daniel S., et al. “Imprisonment and Reoffending.” Crime and Justice, vol. 38, no. 1, 2009. ↑

- See New York v. U.S., 505 U.S. 144, 157 (1992). Under Section 2315 of Title 18, the goods must travel from one state to another to make the crime prosecutable as a federal offense, but the Supreme Court has long held that federal jurisdiction extends to transactions under the Interstate Commerce Clause regardless of whether the specific good has crossed state lines. ↑

- Russell-Einhorn, Malcolm, et al. “Federal-Local Law Enforcement Collaboration in Investigating and Prosecuting Urban Crime, 1982–1999: Drugs, Weapons, and Gangs.” Abt Associates, May 2000. ↑

- Ulrich, Thomas E. “Pretrial Diversion in the Federal Court System.” Federal Probation, vol. 66, no. 3, Dec. 2002. ↑

- See “Deferred Entry Judgment (DEJ)/Diversion.” County of San Mateo. ↑

- Nagin et al., supra. ↑