By Sam Liccardo

The Council and City management has been wrestling with budgetary decisions in recent weeks. As you can read in my March budget message, I’ve prioritized focusing your scarce dollars on addressing homelessness, crime, blight, and resilience, and the Council has approved those priorities as we refine the final budgetary allocations in a vote set for June 14th.

As I’ve conducted dozens of public community meetings to discuss budgetary issues in recent years, many questions and comments can be boiled down to a fundamental concern: ”why can’t San José provide more or better services?” Of course, these questions come in many variations:

- “Can’t we have police officers walking patrol in my neighborhood?”

- “Why are our library hours cut off on Sundays?”

- “Why don’t we have better-maintained parks?”

- “Don’t we pay an enormous amount in taxes, and we live in a wealthy region?”

The answer to all of these questions from justifiably frustrated residents requires some understanding of the chronic budgetary challenges San José has faced for decades.

America’s Most Thinly-Staffed Big City

While the individual performance of particular employees or departments varies for many reasons — and bluntly, we should overlook issues of management or individual effort — the clearest explanation for City Hall’s struggles in providing basic services lies in our persistently low staffing. We have the most thinly-staffed City Hall of any major U.S. city.

Although we made plodding progress in my tenure in restoring services that endured severe cuts, we still have a smaller staff at City Hall today than we did twenty years ago — and they must serve nearly 200,000 more people. This reality can be seen by the graph below, depicting the number of FTE (full-time equivalent) employees citywide:

Here’s the kicker: the reality of chronically thin staffing appears to be even worse than suggested in the bar chart. Why? Because the City must dedicate staff to do things the City never had to do two decades ago. For example, with the creation of San Jose Clean Energy, we had to hire a team to procure green electric power for 350,000 ratepayers. Amid a homelessness crisis, we’re building 1,000 quick-build apartments, and converting hundreds of motel rooms to housing. Through the pandemic, City staff have coordinated the distribution of more than 2 million meals a week to families in need of food, and built out a wi-fi system to provide free wireless broadband to more than 100,000 residents (and to 300,000 residents by the end of this year). Fortunately, new funding sources have supported these efforts, but their prevalence demonstrates how — by default — fewer City staff remain to perform such basic services as police, emergency medical response, libraries, and park maintenance.

So, over the last two decades, City Hall has far fewer people to do much more work for more residents.

Chronic Budgetary Challenges

Why? Our staffing challenges have three primary causes: first, the City’s budget stretches less far paying the higher salaries needed to retain workers in the costly Bay Area, competing against a much more lucrative private sector in Silicon Valley. Second, decades of poor land-use decisions by prior Councils have left San José with a severe jobs-housing imbalance — with the lowest ratio of jobs of any major U.S. city. That leaves San José with much lower tax revenues per capita — as demonstrated by the graphics below — and much greater demand for scarce services:

Recent successes in luring job expansions to San José — with new headquarters or major expansions from Adobe, Apple, Aruba, Broadcom, Google, Micron, Roku, Splunk, Zoom, and many other great employers — will change these numbers over time, but will take a generation to correct.

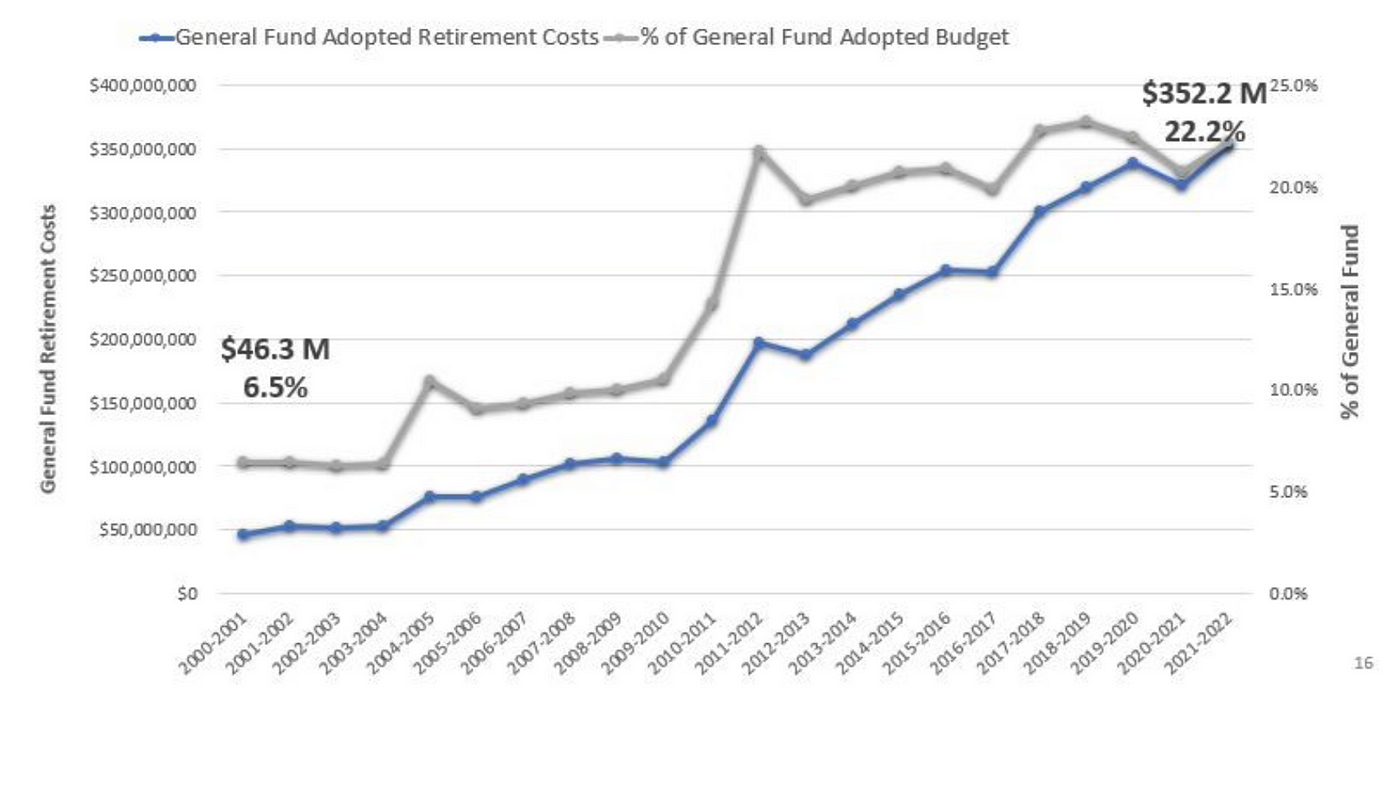

In the last two decades, however, a third challenge has overshadowed all of the others: rapidly rising retirement costs — primarily for pensions and retiree healthcare benefits.

The Problem of Pensions

The collective horror of September 11, 2001, and the heroic response of New York City firefighters and police left a grateful nation believing — understandably — that we needed to take better care of our first responders. California’s elected officials had flush budgets and fully-funded retirement funds to do so. Starting with Governor Gray Davis and the state legislature, elected officials granted increasingly large pension and retiree healthcare benefits to public employees. In San José, the result came in the form of several City Council votes in the early part of that decade to expand benefits for public safety employees and retirees, well in excess of what those same employees could have paid into the system.

In my first weeks in office as a councilmember in 2007, I learned that the problem was deeper-seated. Optimistic assumptions by retirement boards left the public believing that our retirement funds were better funded than they were, and elected officials seeking to curry favor with powerful local unions had no desire to disrupt the wishful thinking. This was not merely true in San José, but in cities and states nationally; everyone happily ignored the unsustainable nature of the generous pension and retiree healthcare promises, while the media and voters didn’t heed the very substantial long-term costs to taxpayers.

Like receding tides, recessions have a way of exposing what has too long lurked hidden on an ocean floor. By 2009, we learned that these decisions had wracked San Jose taxpayers with a $4 billion unfunded liability for pensions and retiree health benefits that would not be covered by employee contributions or investment returns. Paying off that $4 billion debt required an increasingly hefty annual contribution, and annual City pension and retiree healthcare costs quadrupled in a decade. By 2011, they consumed more than $200 million — or nearly a quarter — of our General Fund annually.

The fiscal tail of retirement costs now wagged the dog of the City budget, crowding out spending on many essential services, like fire, police, and emergency medical response. Deficits ballooned, averaging more than $100 million a year. Our workforce and our residents endured a very painful period: layoffs, pay cuts, hiring freezes, and service reductions all contributed to deeply antagonistic political battles. The City and unions discussed reductions in retirement benefits to reduce costs, but negotiations stalled repeatedly amid the acrimony. National media pointed to pension reform skirmishes in San Jose as a harbinger for the challenges that cities, counties, and school districts would grapple with throughout the country.

Then-Mayor Chuck Reed and the Council majority (of which I was one) voted to take the matter to the voters in 2012, in the form of Measure B, to reduce pension benefits. Our voters overwhelmingly — more than 70% — approved Measure B, yet the battle was far from over. One court invalidated a portion of the measure, upholding other parts, sending it back to the City to renegotiate. Meanwhile, some city workers — most visibly police officers — voted with their feet, heading to other local cities with better pay and benefits.

When I became mayor in 2015, we had already lost more than 500 police officers, and had a badly depleted City workforce, and still lacked budgetary flexibility to restore services.

We looked for ways to salvage fiscal savings from the partially invalidated Measure B without exacerbating the exodus of police officers and other talented city staff. We went back to the negotiating table with our unions — as required by state law — and engaged in many intense months of difficult negotiations.

The Breakthrough

Although many media accounts about pension reforms focused on pensions, about half of the retirement debt incurred by cities like San Jose came from retiree medical benefits, which had a $1.6 billion retiree medical unfunded liability by 2009. A key breakthrough came when the police union recognized — and other unions came around to the view — that the retiree health benefits were becoming not only too costly for taxpayers, but for their employees as well. The emergence of ObamaCare at the federal level smoothed the transition to Medicare for retired workers, and an important insight emerged: everyone could do better by simply abandoning the City retiree medical benefit. Although state law required the preservation of “vested benefits” for existing employees, the City could close the plan to new hires and save millions annually.

That breakthrough provided early momentum for negotiations. In the following months, lead City negotiator Jennifer Schembri and dedicated union leaders tirelessly negotiated an end to pension “bonus checks,” a reduction in pensions for new hires, and the closure of the retiree healthcare plans. An independent actuary estimated that the package would save taxpayers some $3 billion over the next three decades — as many savings as was achieved with the 2012 Measure B, but achieved entirely through negotiation. Every employee bargaining group signed the agreement, the Council approved it, and we took it back to the voters in November of 2016, as the new “Measure B.”

Voters approved the deal, and we were on our way. Yet the benefits to taxpayers and city services would take many years to materialize. We continued to struggle with rising retirement costs after the 2016 Measure B, until the number of newly hired employees could alter the trajectory of long-term retirement costs.

The Payoff — and The Future

The hard reset of retirement costs in 2012 and 2016 interrupted two decades of recession- and pension-driven deficits (expressed in millions of General Fund dollars in the chart below), with seven years of budgetary stability, until the pandemic wrought its own fiscal challenges:

Yet this year — for the first time in two decades — the City Manager’s Budget Office issued projections for budget surpluses, albeit modest, for the next five years:

What’s driving the good news? While revenues have rebounded faster than expected, one key factor above all explains these surpluses: falling retirement costs.

That is, we finally reached the crest of the wave. Annual retirement fund contributions decline in our actuarial projections in each of the next ten years. For example, in the Police and Fire Retirement Fund, the actuary updated its 2020 projections earlier this year, to offer the following picture:

The market’s steep fall this year will reduce overall retirement fund returns, to be sure, and may shift the curve slightly to the right, but a single year’s losses will not severely affect the funds’ long-term funding status. The long-awaited dividend for our residents and employees will come. That benefit will arrive in the form of discretionary dollars to improve services, infrastructure, positions, and wages in the years ahead.

Before celebrating, disclaimers are required. First, these are projected dollars. They’re a far cry from real dollars, which only materialize when the projected year becomes an actual year, and reality supplants all of the assumptions in the budgetary model. Still, we never saw any sustained projected surpluses previously. Second, the pandemic and our recovery forced the City to expand services such as trash cleanups, food distribution, child care, and small business support. As in any emergency, we relied on one-time sources, such as federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan, to deal with crises. Now, we either need to cut those services or absorb them on an ongoing basis into a constrained City budget. That requires belt-tightening. Finally, we’ve recently invested in many new public assets that require new staff to operate and maintain them, such as Measure T’s new fire stations and Emergency Operations Center, or new parks funded by local housing development.

In short, preserving our essential services — and growing them in future years — requires us to wrestle with what we call a “service level deficit,” and yet more belt-tightening:

Yet we should happily take this problem over that of the last couple of decades. We can actually see the light at the end of the tunnel — and it’s not an oncoming train.

Unhappily, many external forces can disrupt projections like these. Recession, wars in Europe, a reprisal of a more deadly COVID variant, inflation, and rising interest rates can all wreak havoc on a city’s budget. These external factors lie beyond our control, of course, but we must prepare for them.

External factors should concern us, but what should concern us more — particularly as we consider a transition in City leadership — are those factors we control. As the last decade’s battles over ballooning retirement costs instruct, we often incur our worst suffering at our own hands. Let’s hope that our future leadership embraces history’s lesson.